Anat Shahar on What Makes a Planet Habitable

Since all forms of life on Earth require liquid water, at least at some stage in their life cycle, it is natural to suppose that in order to be habitable, an exoplanet should also have liquid water. While much of the public discussion has focused on constraining the so-called Goldilocks zone, i.e., not too hot nor too cold for liquid water to exist, an equally key issue is how a planet would get its water in the first place. In the podcast, Anat Shahar explains how her modeling and experiments predict that plenty of water would form as a result of chemical reactions between the hydrogen atmospheres observed on many exoplanets and the magma ocean with which planets initially form.

Shahar is a Staff Scientist and Deputy for Research Advancement at the Earth and Planets Laboratory at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, DC.

Photo: Badro Lab at IPGP, Paris

Podcast Illustrations

All images courtesy of Anat Shahar unless otherwise noted.

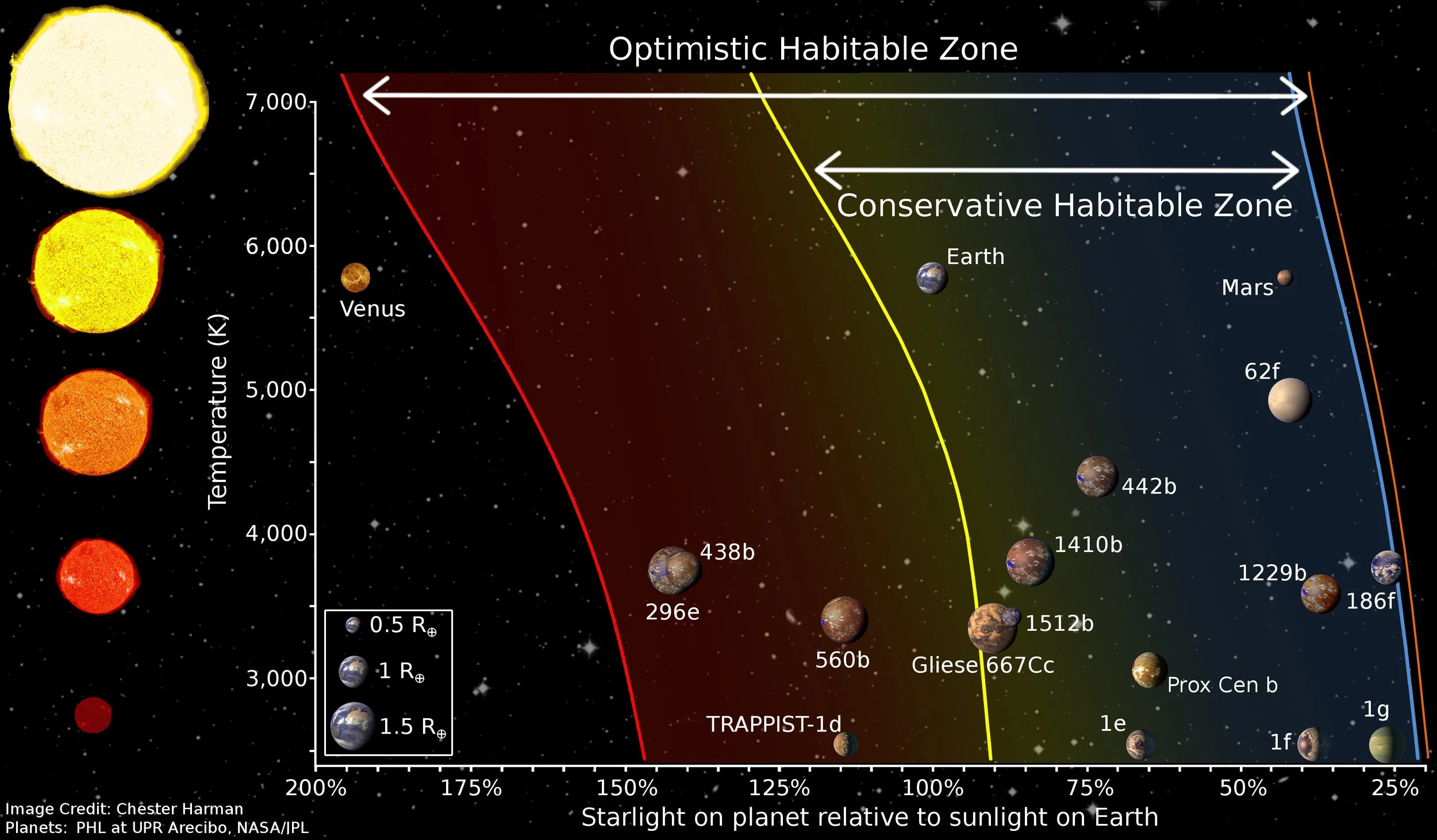

Diagram showing the boundaries of the habitable zone for stars of different surface temperatures. The habitable zone is defined as the zone in which liquid water can exist. The models on which these results are based include the effects of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, tidal locking, and other effects, some of which involve complex feedback mechanisms. These effects mean that at any given level of starlight incident on the planet, the habitable zone boundaries depend upon the temperature of the star, which is why the habitable zone boundaries are curved in the diagram. Various planets within our solar system are shown, along with selected exoplanets.

Kasting, J.F., et al. (2013), PNAS 111 (35) 12641

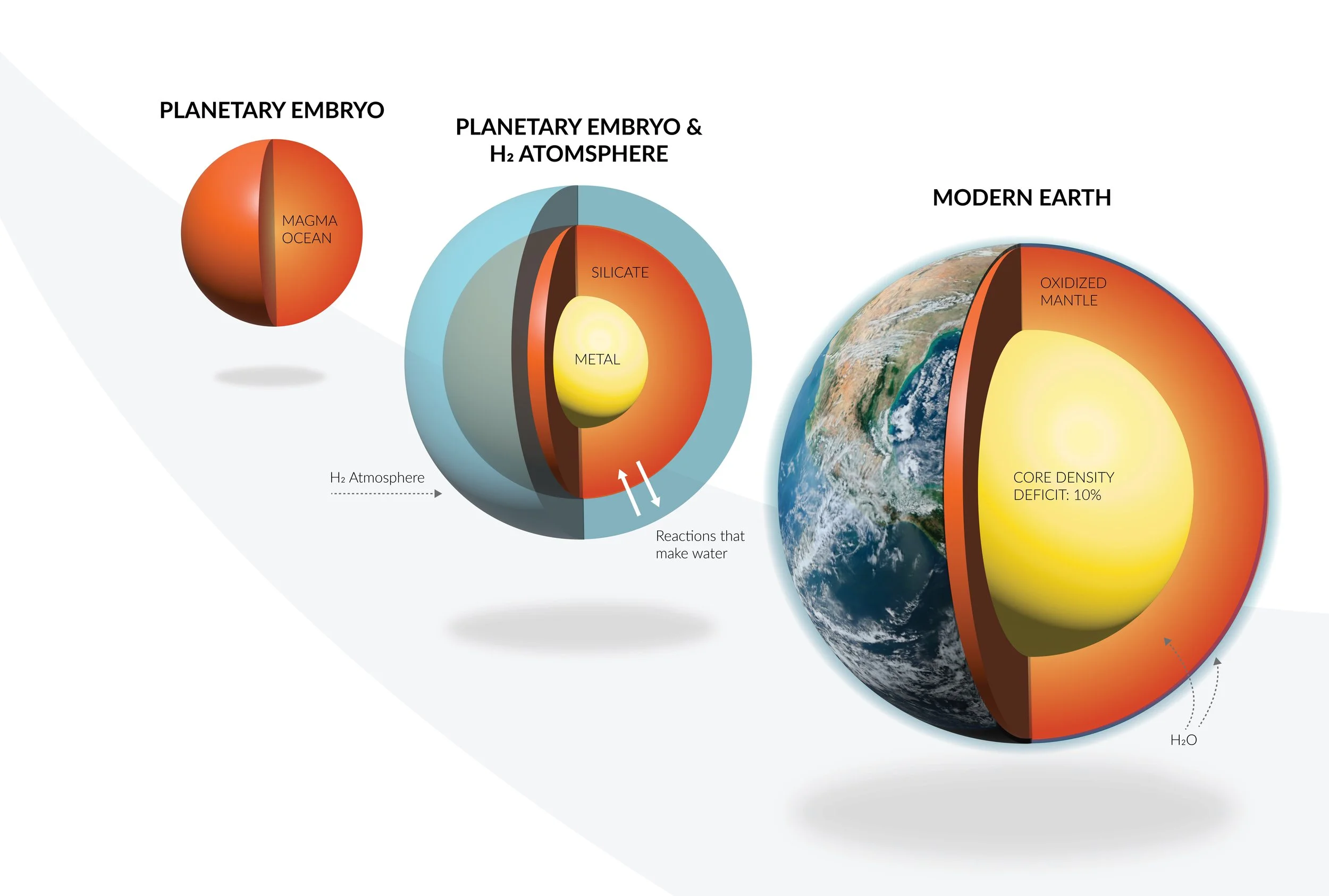

Stages in the evolution of Earth. Left: planetary embryo that is too small to retain an atmosphere. Center: the protoplanet grows to a size at which it can accrete a hydrogen atmosphere and differentiate into a metallic core and molten silicate mantle. It is in this stage that the water-producing chemical reactions between the atmosphere and magma ocean described in the podcast take place. Right: modern Earth with a metallic core, oxidized mantle, and water in the mantle, lithosphere (not shown), and atmosphere. The core density is 10 percent lighter than it would be if it was pure iron, implying that there are some light elements in the core.

Illustration by Edward Young/UCLA and Katherine Cain/Carnegie Institution for Science

Experiments

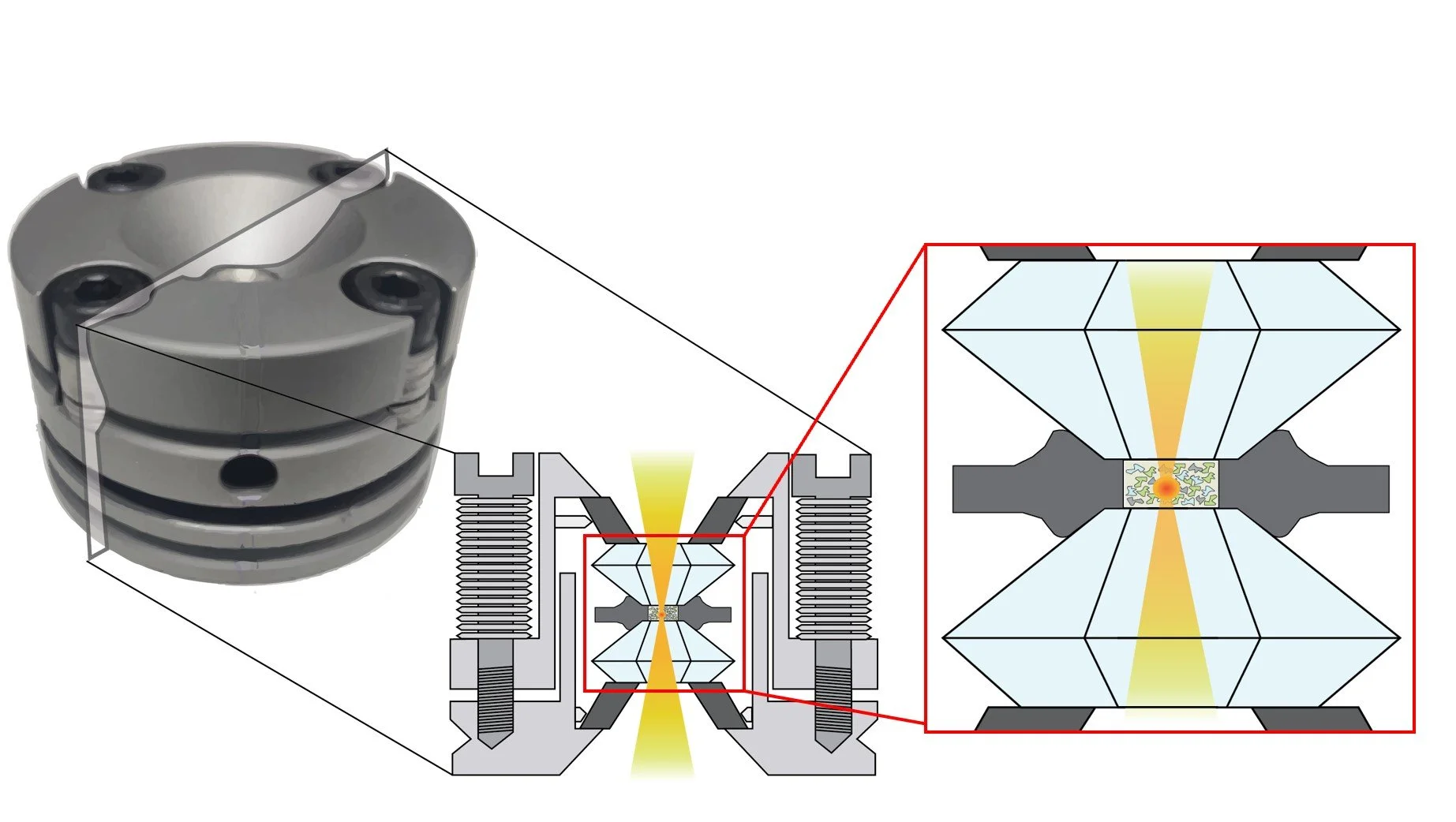

Diagram of the diamond anvil compressor used in Shahar’s high-pressure experiments that simulate conditions on large planets. The inset (right) of the diamond assembly is about 5 mm across. The entire diamond anvil compressor is 6 cm high and 3 cm across. The diamonds compress the sample up to a pressure between 16 and 60 GPa. Lasers above and below are directed onto the sample, heating it to temperatures of 4,000 K and above.

Courtesy of Francesca Miozzi

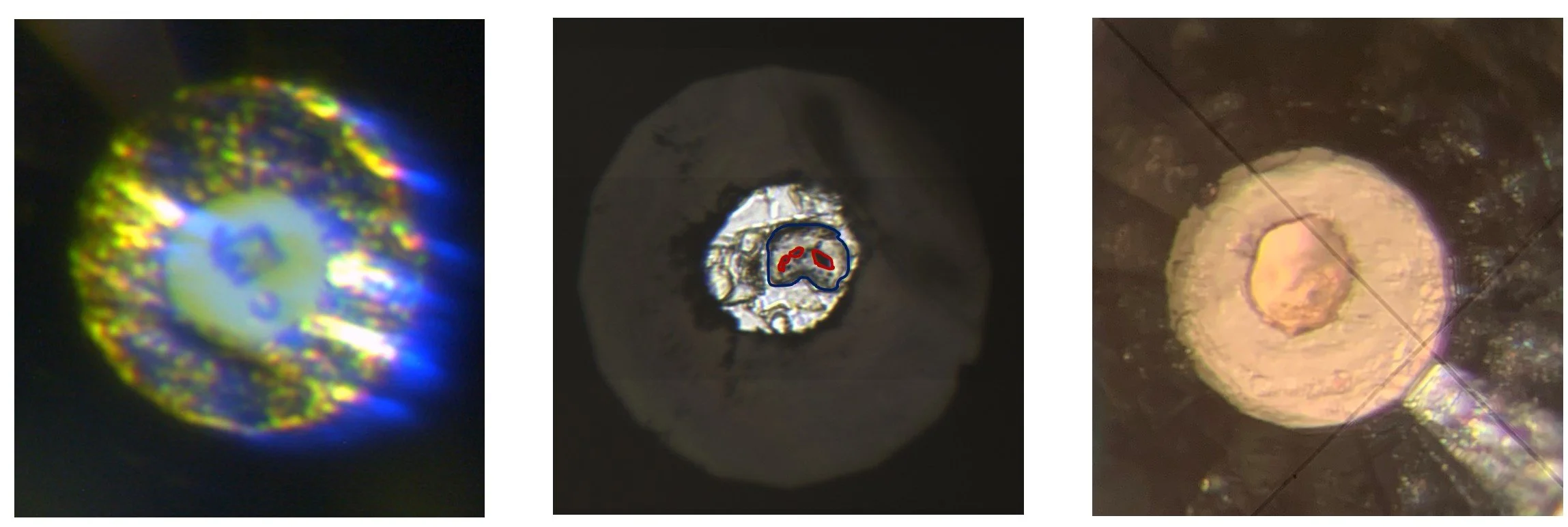

Photomicrograph of the diamond anvil used in Shahar’s high-pressure experiments. Between the diamond tips is a gasket that holds a silicate magma ocean-like sample prepared in the lab and the hydrogen. The diamonds are between 1/2 to 1 carat in size with the tip facing the sample being about 300 microns across.

Left: photomicrograph showing the sample of simulated mantle material in the inner region surrounded by the gasket. Center: sample after heating. The colorful part is the melt. Right: sample following removal from the diamond anvil compressor with resin added to keep the sample intact and extractable for subsequent analysis.

Courtesy of Francesca Miozzi

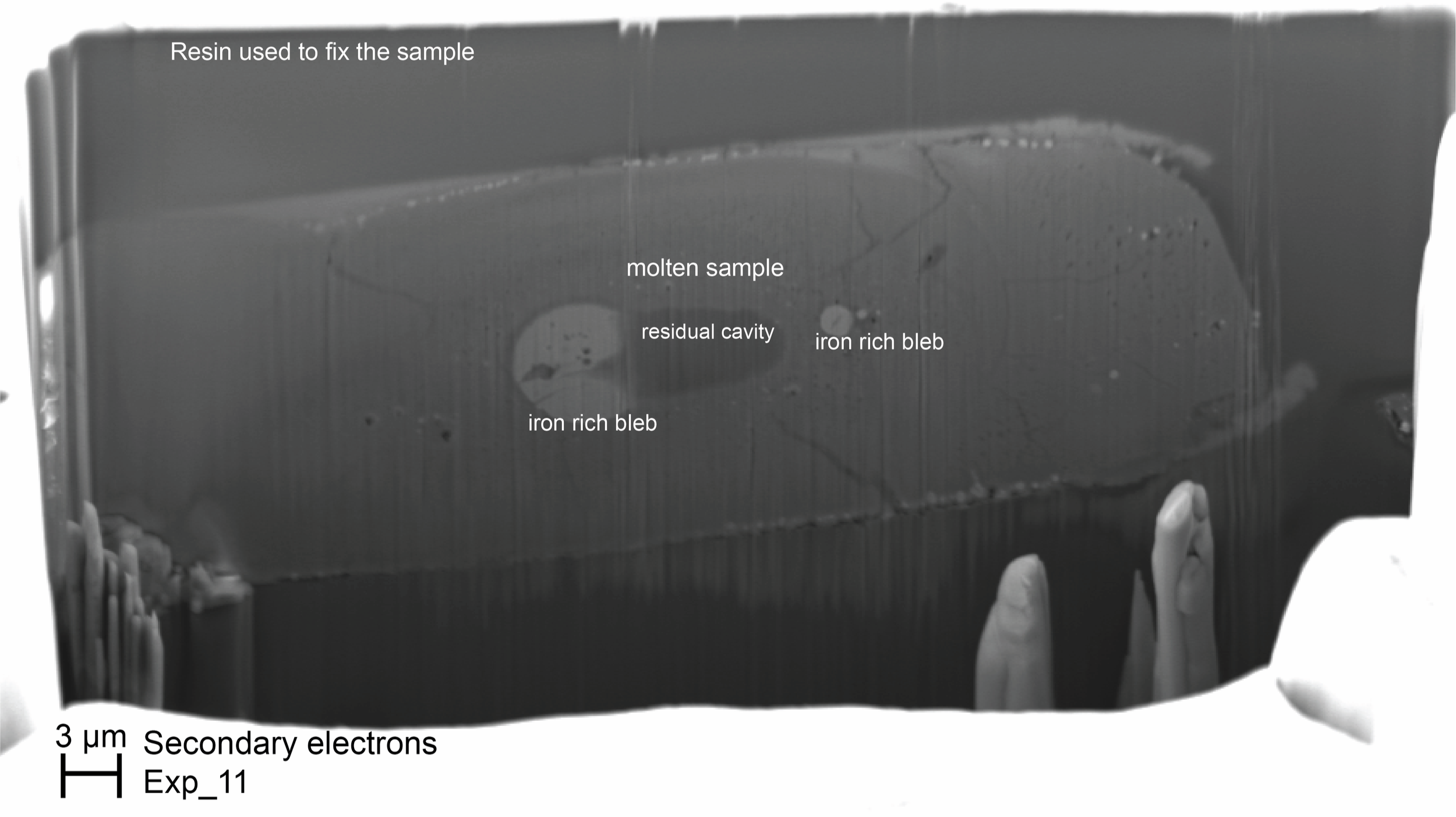

Electron microscope image of a sample after it was subjected to high temperature and pressure in the presence of hydrogen. The residual cavity is where water was created. The iron-rich bleb was formed when the iron oxide (FeO) was reduced by the hydrogen during the water-forming process, as shown in the next figure at left.

Courtesy of Francesca Miozzi

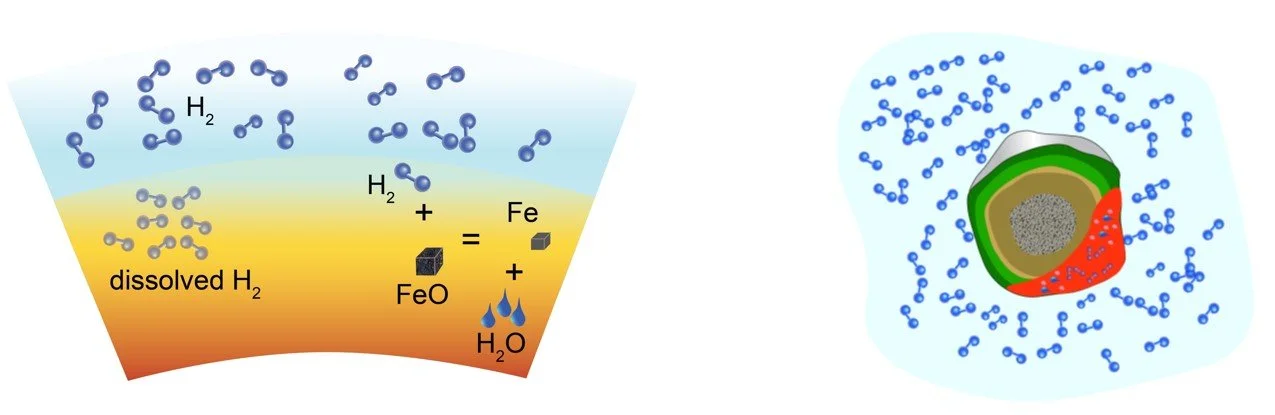

Interaction of a hydrogen-rich gas with a magma ocean. Left: hydrogen dissolves in the magma ocean and water is produced in the magma through the reduction of iron oxide. Right: on a small body that is not fully molten, water may be produced only where molten magma (red) is present. The other colors represent the rest of the differentiated planetesimal.

Courtesy of Francesca Miozzi

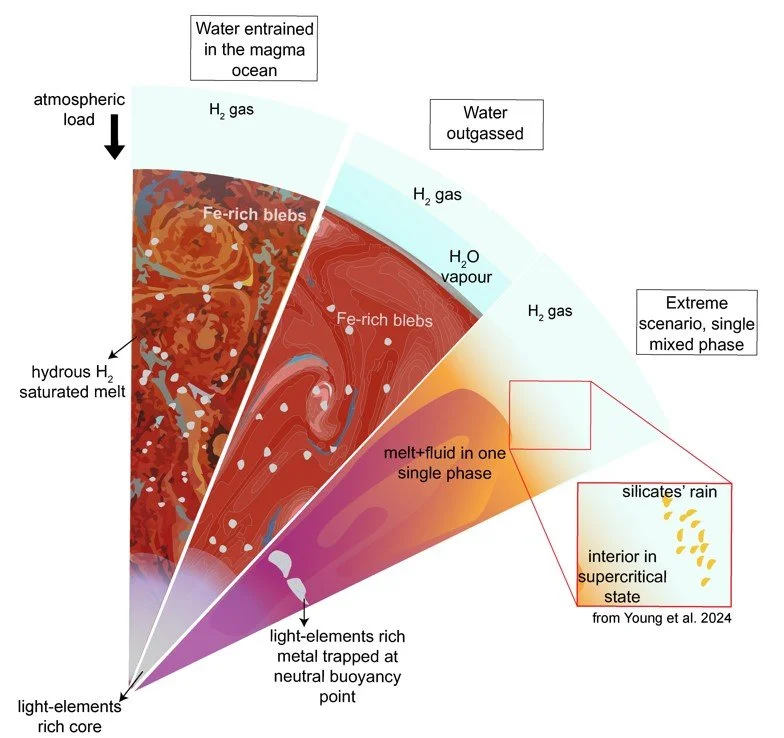

Conceptual illustration of three possible scenarios for interior–atmosphere interaction in big planetary bodies, often referred to as sub-Neptunes (between 1 and 17 Earth masses). Left: free fluid water and Fe-enriched blebs are entrained in the magma ocean. Centre: water is outgassed to create a steam atmosphere while the Fe-enriched blebs sink toward the centre. Right: extreme scenario in which all phases are miscible.

Courtesy of Francesca Miozzi