Carina Hoorn on the Evolution of the Amazon Basin

Listen to the podcast here or wherever you get your podcasts.

The Amazon Basin is the most biodiverse region on Earth, being the home of one in five of all bird species, one in five of all fish species, and over 40,000 plant species. In the podcast, Carina Hoorn explains how the rise of the Andes and marine incursions drove an increase in biodiversity in the Early Miocene. This involved the arrival of fresh river-borne sediments from the eroding mountains and the diversification of aqueous environments caused by influxes of salt water during the marine incursions.

Hoorn is an Associate Professor in the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics at the University of Amsterdam and Research Associate at the Negaunee Integrative Research Center, Earth Science Section, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

Photo: Daniel Winitsky

Podcast Illustrations

Illustrations courtesy of Carina Hoorn unless otherwise indicated.

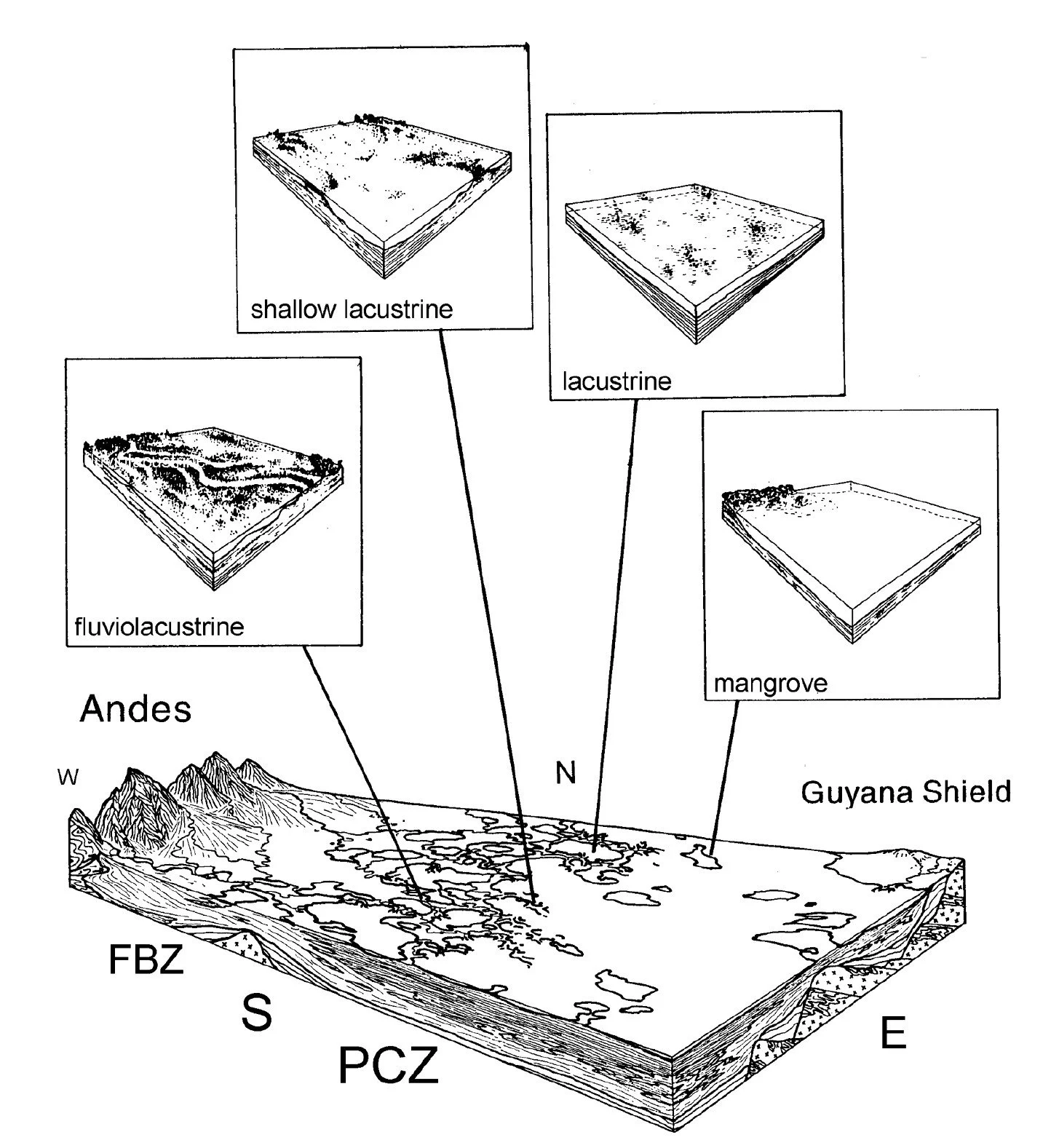

Aqueous Environments of the Pebas System

In the podcast, Hoorn describes the various aqueous environments that prevailed in the Pebas Wetlands System. Lacustrine: freshwater lake environment; fluvio-lacustrine: part lake and part stream waters; estuarine: raised salinity in a lacustrine system; mangrove: shallow saline environments where mangrove trees line the shore. While the Pebas system has no close modern analogue, the Brazilian Pantanal and the Florida Everglades are probably the closest. FBZ: Foreland Basin Zone; PCZ: Pericratonic Zone.

Wesselingh, F.P. et al. (2001), Cainozoic Research, 1(1-2) 35

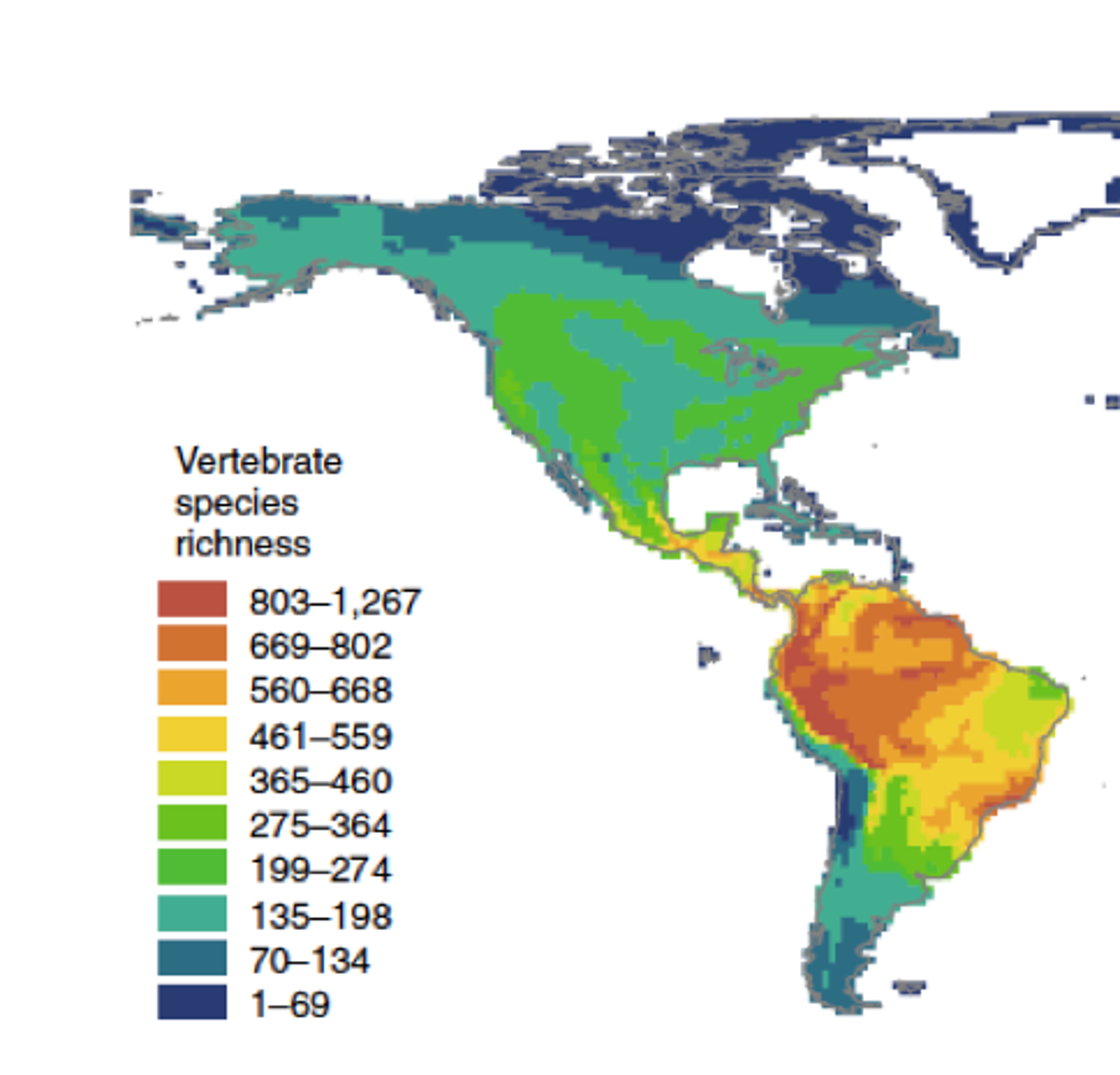

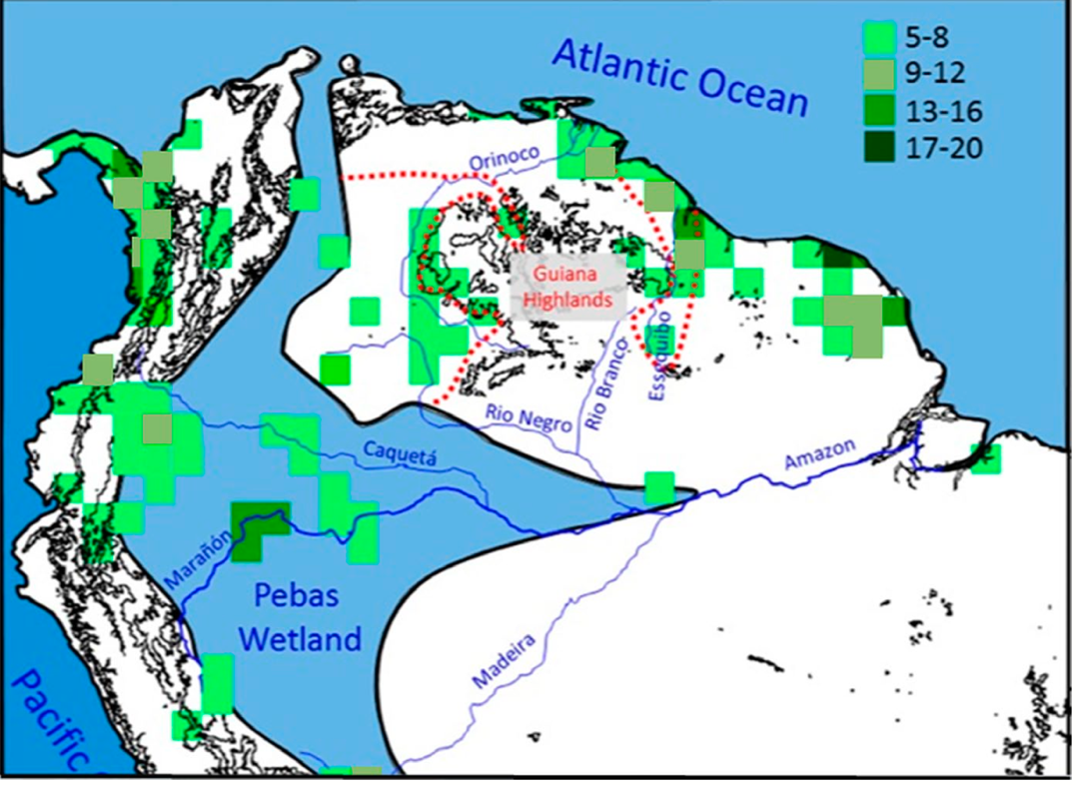

Map showing present-day average number of vertebrate species per square km.

Antonelli, A. et al. (2018), Nature Geoscience 11, 718

Amazonian blackwater lake (left), rainforest, and whitewater river. The whitewater river is laden with sediments from erosion of the Andes.

Photo Rhett A. Butler for Mongabay

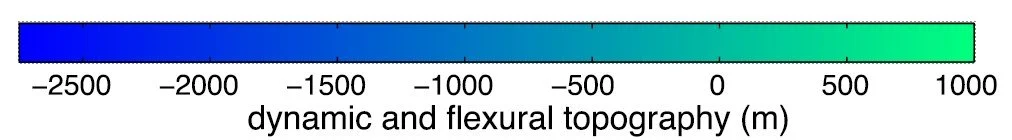

In the podcast, Hoorn attributes some of the rise of the Andes and subsidence of the Amazon basin to the flat slab subduction of the Nazca plate under the west coast of South America. The flexural and dynamic effects of the subduction have been modeled and support the idea that the subduction could have driven the topographic and sedimentary evolution of the western Amazon since the Miocene, eventually shaping the present-day landscape. Left: map of the topography calculated by models of the flexural and dynamic effects of the subduction. Turquoise arrows represent drainage directions. The thin dotted line represents the approximate location of the cartoon cross section shown at right. Right: modeled cross section with gray dotted regions indicate sedimentary infill, with region 1 indicating the oldest deposits and 3 the youngest. The letters I and P on the cross sections mark the estimated locations of the Iquitos and Purus Arches.

Eakin, C. M. et al. (2014), 404, 250

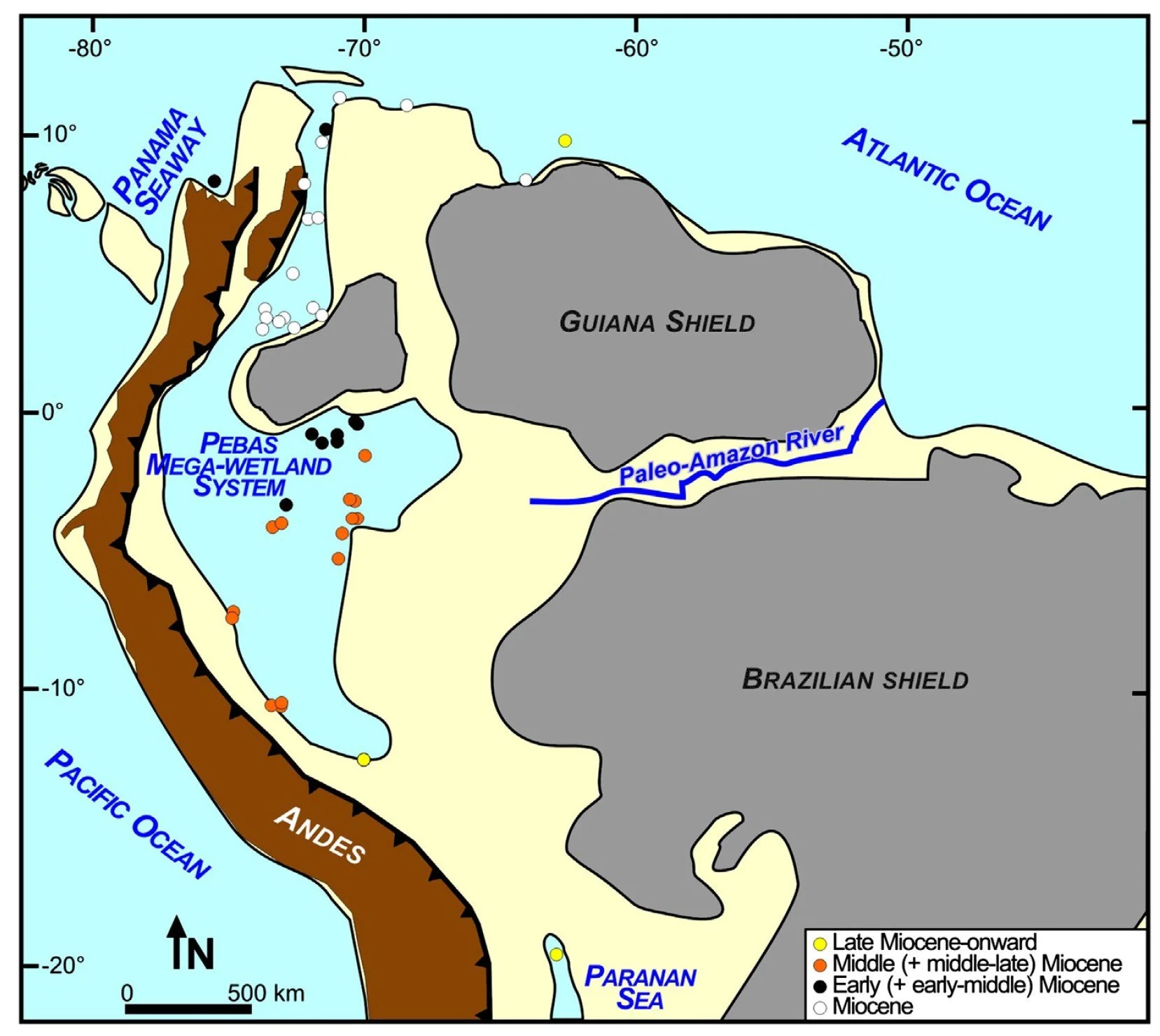

Map of northern South America during the Miocene (23 - 5.3 million years ago). It shows the reconstructed extent of the Pebas wetland system, which Hoorn discusses in the podcast.

The Pebas wetland acted as a barrier to the dispersal for most mammals and plants, but was a permeable system for certain plants as well as fish, and aquatic mammal taxa.

Boonstra, M. et al. (2015), Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 417, 176

Miocene Fossils from the Pebas Wetlands

Outcrops along the Colombia stretch of the Amazon River at Los Chorros with Miocene fossils from the Pebas wetlands.

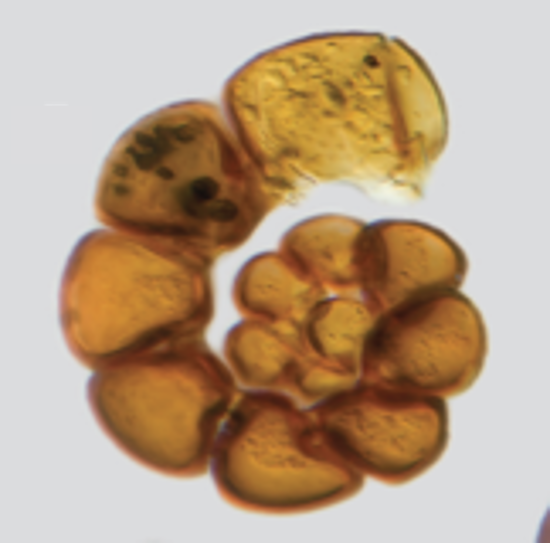

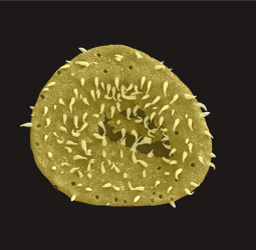

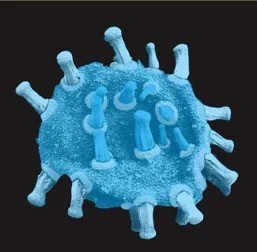

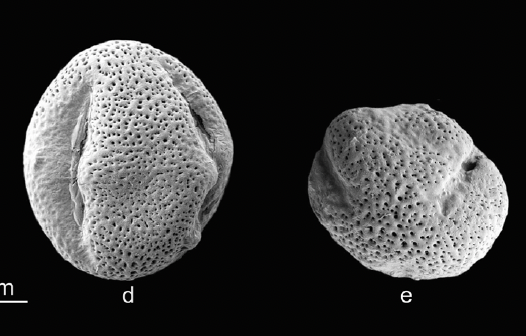

Miocene fossils from the Pebas Wetland System. These species are characteristic of lacustrine-estuarine conditions with wetland vegetation, peripheral forest, and a diverse aquatic fauna. Top from left to right: microforaminifer microfossils (70 µm across), two fossil palm pollen grains (each 40 µm across), and mangrove pollen (each 25 µm across). Bottom left: gastropod (length 12 mm, photo Frank Wesselingh). Bottom right: cast of the skull of Purussaurus brasiliensis, Upper Miocene in dorsal (upper) and left lateral (lower) views. Scale bar = 30 cm. An artist rendering of Purussaurus appears below. (photo O. Aguilera).

Mangrove pollen: Sciumbata, M. et al. (2021), Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 101(1), 123

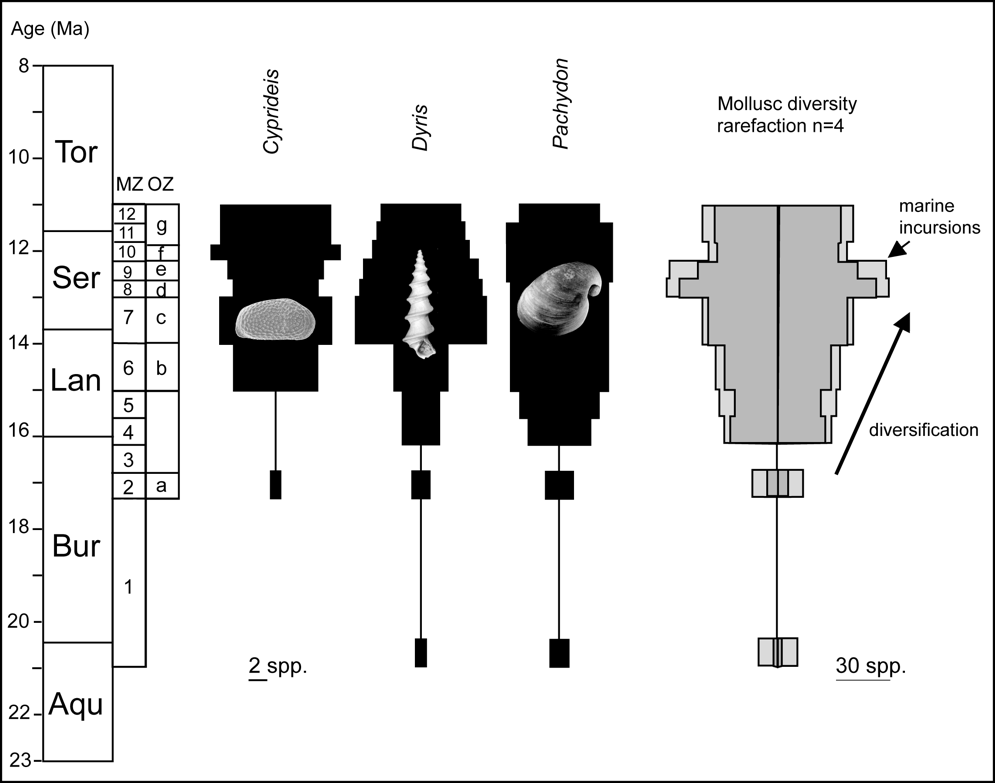

Molluscs and ostracods radiated in the Amazon wetland. This diversification accompanied the development of a freshwater wetland with episodic marine influence. The marine influence varied in nature across the wetland and included tidal features and mangroves.

Wesselingh, F. P. and Ramos, M.. I. (2010), Amazonian aquatic invertebrate faunas (Mollusca, Ostracoda) and their development over the past 30 million years. In: Hoorn C., Wesselingh F.P., editors. Amazonia, Landscape and Species Evolution: a Look into the Past. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford: 2010, 302

In the Miocene, the Amazon basin had a rich diversity of reptiles. The picture is a life reconstruction of a young to sub-adult Purussaurus attacking a ground sloth Pseudoprepotherium in a swamp of proto-Amazonia.

Jorge A. González

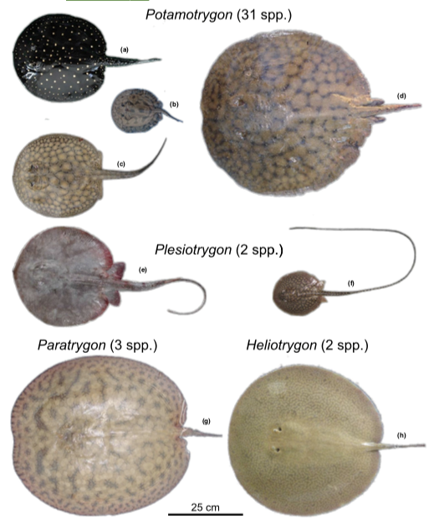

Marine fish that reached the Amazon during the Miocene marine incursions settled and diversified.

Fontanelle, J.. P. et al. (2021), Journal of Biogeography, 48(6), 1406

The neotropical freshwater sting-rays are an example of a family that arrived during marine incursions that occurred during the Oligocene/Miocene.

@OneEarth

The Amazon pink dolphin Inia geoffrensis is derived from a marine species.

Michel Viard

Map showing the number of coastal species in the region of each shaded box. These owe their existence here to the marine incursions.

Bernal, R. et al. (2019), Journal of Biogeography, 46(8), 1749

Modern plants that are still distributed in the former marine incursion pathway, which is thought to have left a geochemical imprint in the soils on top of the Solimões/Pebas formation. It has been shown that the bedrock and soils of the Pebas/Amazonas are much richer due either to general chemistry or chemistry related to marine incursions.

Core Samples

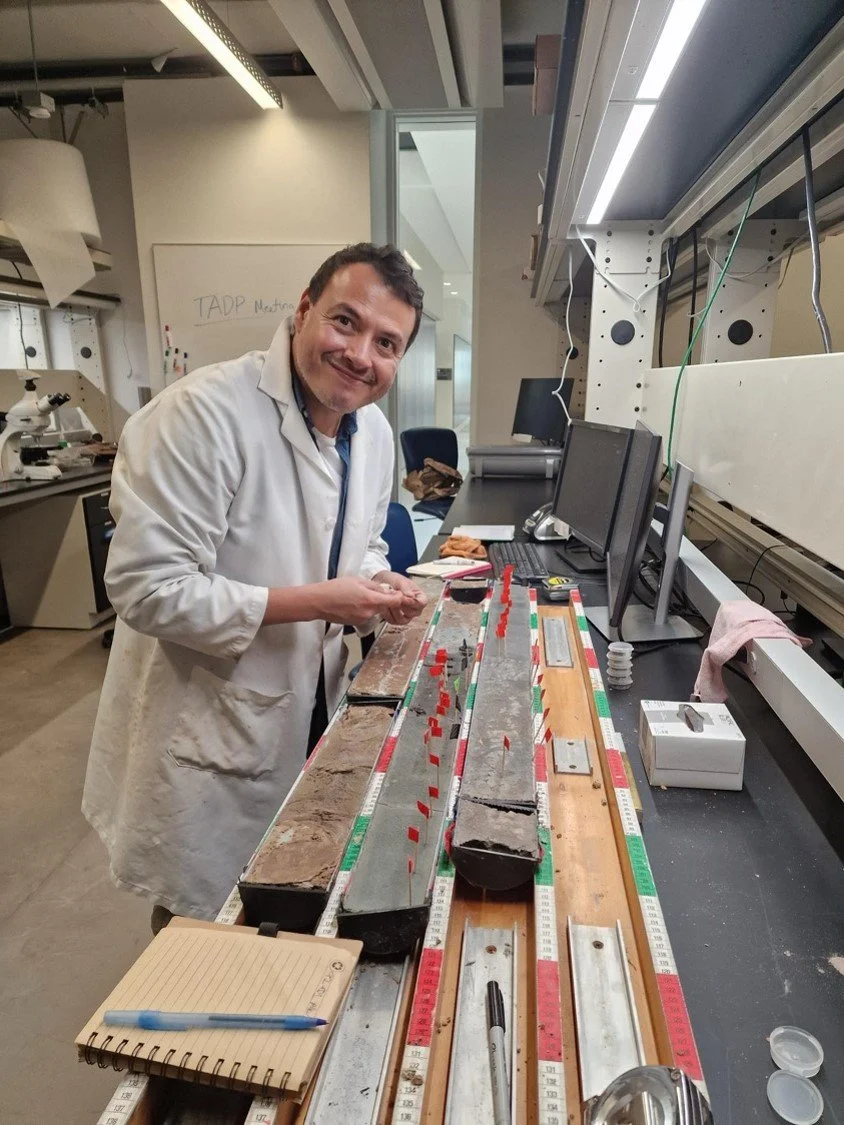

TransAmazon Drilling Project site in the Acre Basin, Municipality of Rodrigues Alves (AC). The core was drilled for scientific purposes only so as to help us understand the history of the Amazon environment and biodiversity. The drilling reached a depth of 923 meters.

Isaac Bezerra

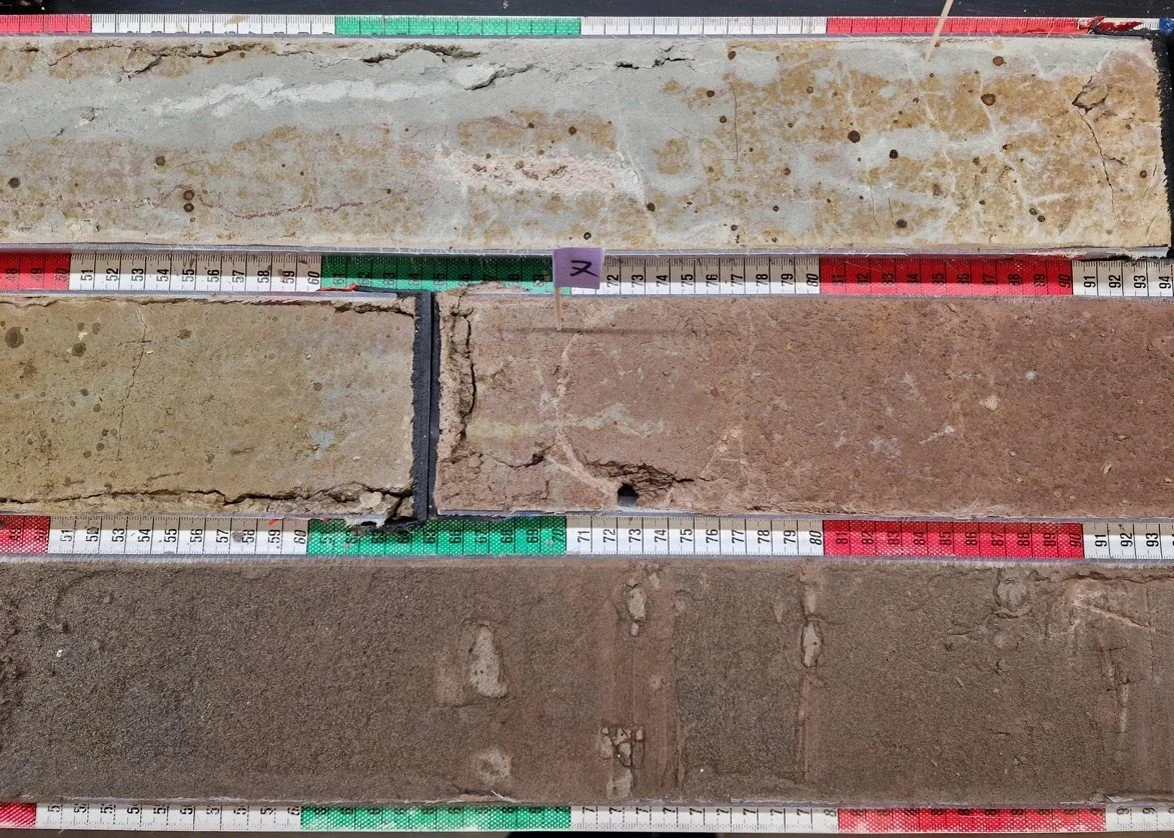

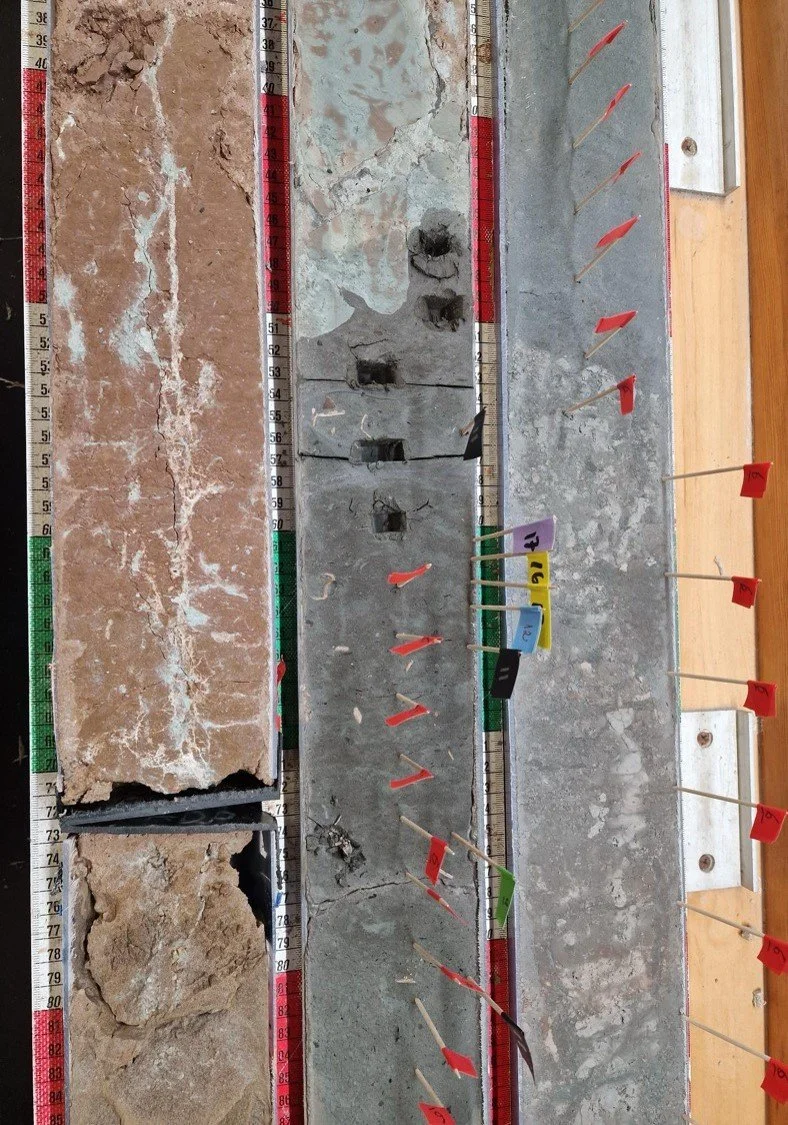

Portions of the drill core comprising fluvial deposits and paleosols. The red colors and the mottling are typical for tropical soils. The context suggests the location was an abandoned river channel.

The red flags mark pollen samples, which are adhered to clay particles deposited in environments such as fluvial overbanks and floodplains. Hoorn’s collaborator Angelo Plata-Torres is pictured.