Keith Klepeis on How Plutons Form

Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts.

Plutons are bodies of igneous rock that crystallize from magma at depth below the Earth’s surface. But even though this magma never makes it to the surface, it still has to travel many kilometers up from its source near the base of the crust to the upper crust where plutons form. In the podcast, Keith Klepeis explains how it makes that journey and describes the shape of the resulting structures. Many of his findings come from one region in particular that provides an exceptional window into the origin, evolution, and structure of plutons — the Southern Fiordland region of New Zealand’s South Island.

Klepeis is a Professor in the Department of Geography and Geosciences at the University of Vermont.

Podcast Illustrations

All images courtesy of Keith Klepeis unless otherwise noted.

In addition to Klepeis, the Southern Fiordland project team included Joshua Schwartz, Elena Miranda, Rose Turnbull, and Richard Jongens.

The Southern Fiordland region of New Zealand’s South Island. The region exposes a large batholith called the Median Batholith, but the only adequate exposures of rock in this rugged temperate rain forest are along the fjord coastlines and above the treeline near the peaks. In the podcast, Klepeis explains how they relied on boats and helicopters to do their fieldwork.

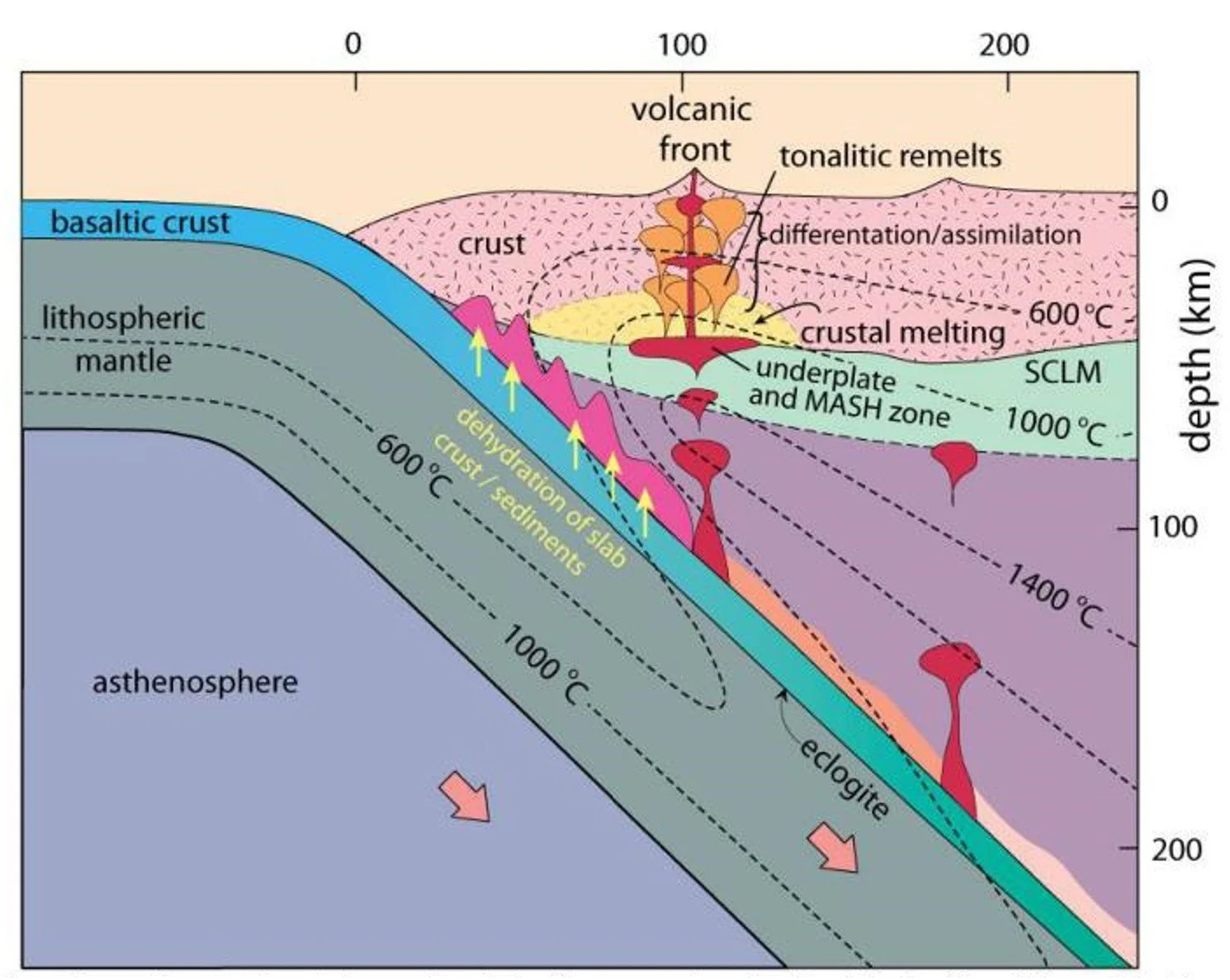

Subduction Zone

Most plutons form above a subducting oceanic plate. Once it reaches a depth of about 150 km, the subducting lithosphere with its basalts and sediments undergoes dehydration reactions that liberate water. The water rises and, when it travels through the overriding mantle wedge, reduces the melting temperature to about 1,000 C, with the result that magma is created. While some magma reaches the surface and forms a Cordilleran volcanic arc, the remainder cools at depth, forming the plutons and their associated structures that Klepeis describes in the podcast.

Adapted from Lillie, R.J. (2005), Parks and Plates: The Geology of our National Parks, Monuments, and Seashores

Diagrammatic cross section through the continental crust across a subduction zone showing a volcanic system with its underlying feeder dikes and batholith. Basaltic magmas pool at the base of the crust where they differentiate and melt crustal rocks. According to the currently favored “Mush” model, this happens without chemical interaction with the surrounding material More evolved andesitic magmas then rise to the middle crust forming granitic batholith complexes. Magmatic fluids continue to ascend through the crust and may form a shallow pre-eruptive chamber. The figure shows the mushroom-like shapes of the crustal melt/crystal mix described in the podcast. The MOHO is the boundary between the crust (pale green) and mantle lithosphere (purple). The mantle wedge is pale grey/blue region between the subducting crust and the mantle lithosphere. Plutons form as part of the batholithic complex shown in the shallow crust.

Richards, J. P. (2011), Ore Geology Reviews, v. 40, 1

Schematic cross section of an active continental margin subduction zone, showing the dehydration of the subducting slab, hydration and melting of a heterogeneous mantle wedge (including enriched sub-continental lithospheric mantle), and crustal underplating of mantle-derived melts. Remelting of the underplate to produce tonalitic magmas and a possible of crustal melting are also shown. As magmas pass through the continental crust they may differentiate further and/or assimilate continental crust.

Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology, Prentice Hall

The Median Batholith

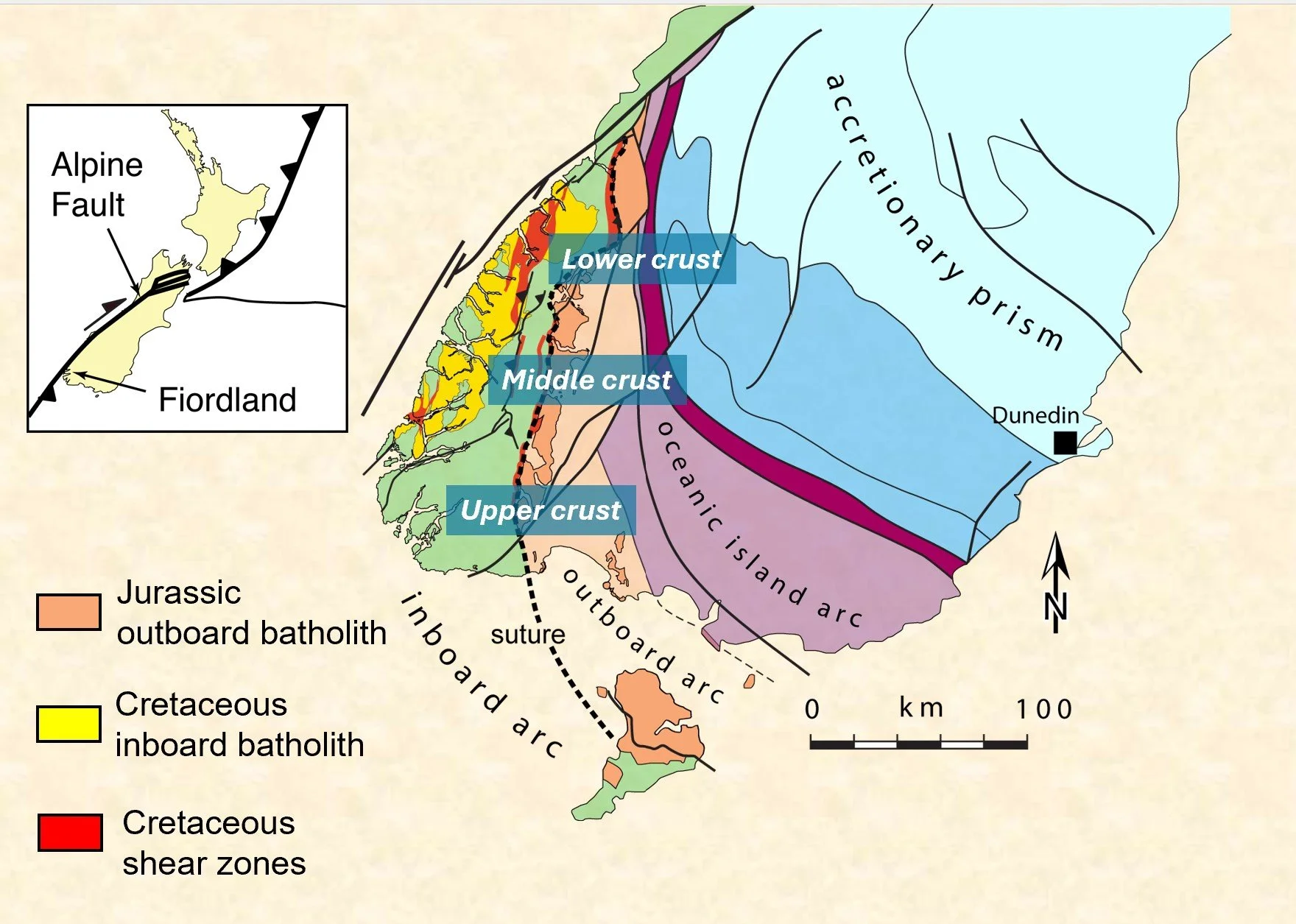

Klepeis and his team focused their recent research on the Median Batholith (shaded red) in the South Fiordland region of New Zealand. Today, the batholith is offset by the Alpine Fault. The inset at bottom right shows a reconstruction of the batholith prior to 37 million years ago.

Geological map of Southern Fiordland. The map labels the lower, middle, and upper crustal regions that are all exposed thanks to tilting caused by compressional faulting along the Alpine Fault (black line running along the western coast). This unique geometry enabled Klepeis and his team to map the 3-dimensional structure of the crust and reveal the conduit and mushroom-like sheet structure of the intruding magma.

Klepeis, K. A. et al. (2022) Tectonics, 41, e2021TC007097

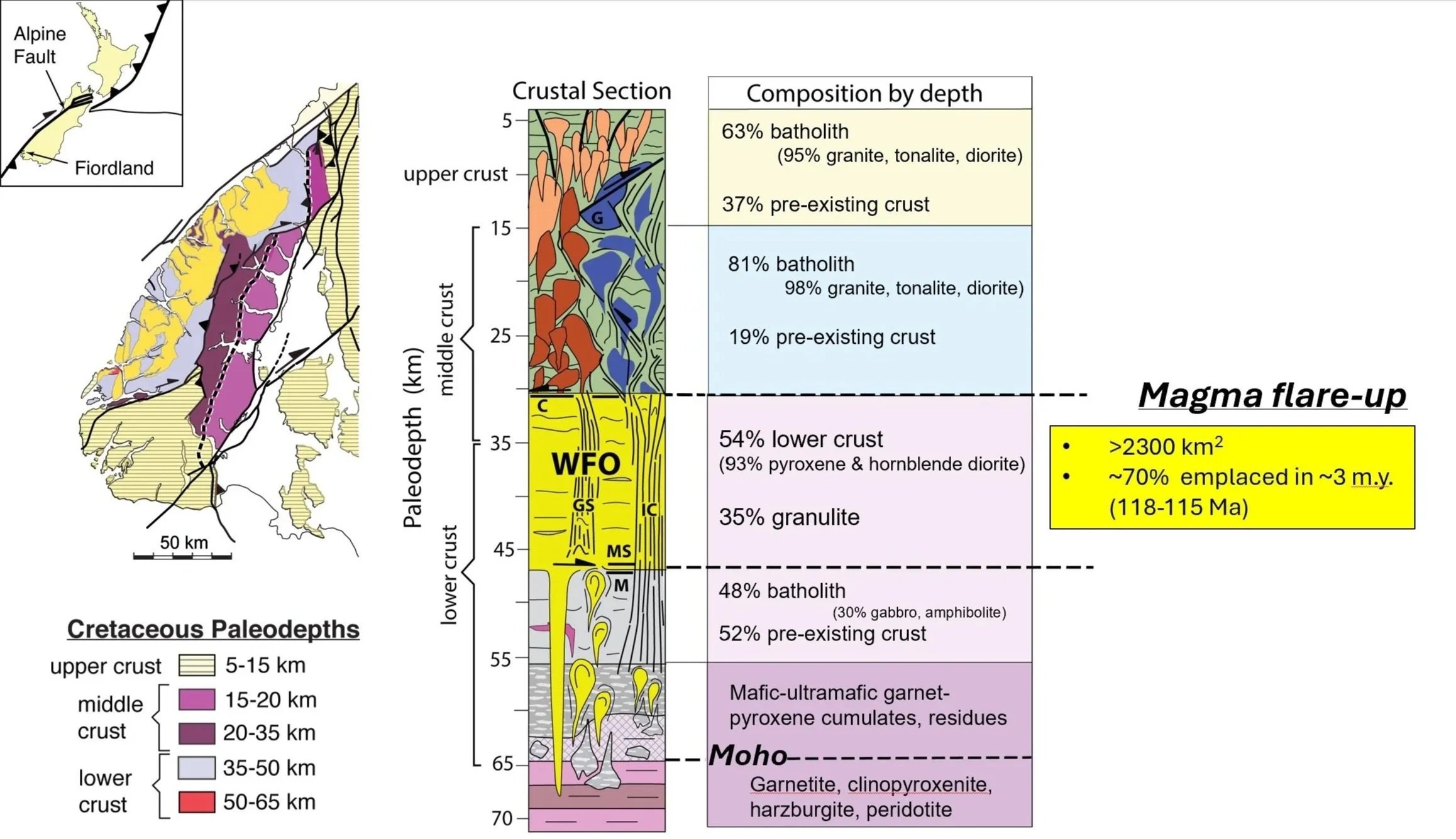

Reconstructing the crustal section of the Southern Fiordland magmatic arc. The map on the left shows Fiordland shaded by its depth during the Cretaceous. The deepest exposures are on the west side, shaded in purple and yellow. The crustal section in the center is a diagrammatic representation of the structure and is annotated at right with its composition, showing that the crust becomes Increasingly mafic with depth. The upper crust (above 30 km) is mainly granite, tonalite, and diorite forming bulbous and/or steep-sided bodies. Below 30-km depth, there are layered sheets. In the middle crust is the Western Fiordland Orthogneiss (WFO), which is a major part of the Median batholith. The Misty pluton, which Klepeis mentions in the podcast, is a part of the WFO. This section represents a major magma flare-up, covering about 2,300 sq km, of which 70 percent was emplaced in just 3 million years.

Image: Klepeis, K. A. et al. (2022) Tectonics, 41, e2021TC007097

Timing of emplacement: Schwartz, J. J. et al. (2017), Lithosphere, 9(3), 343

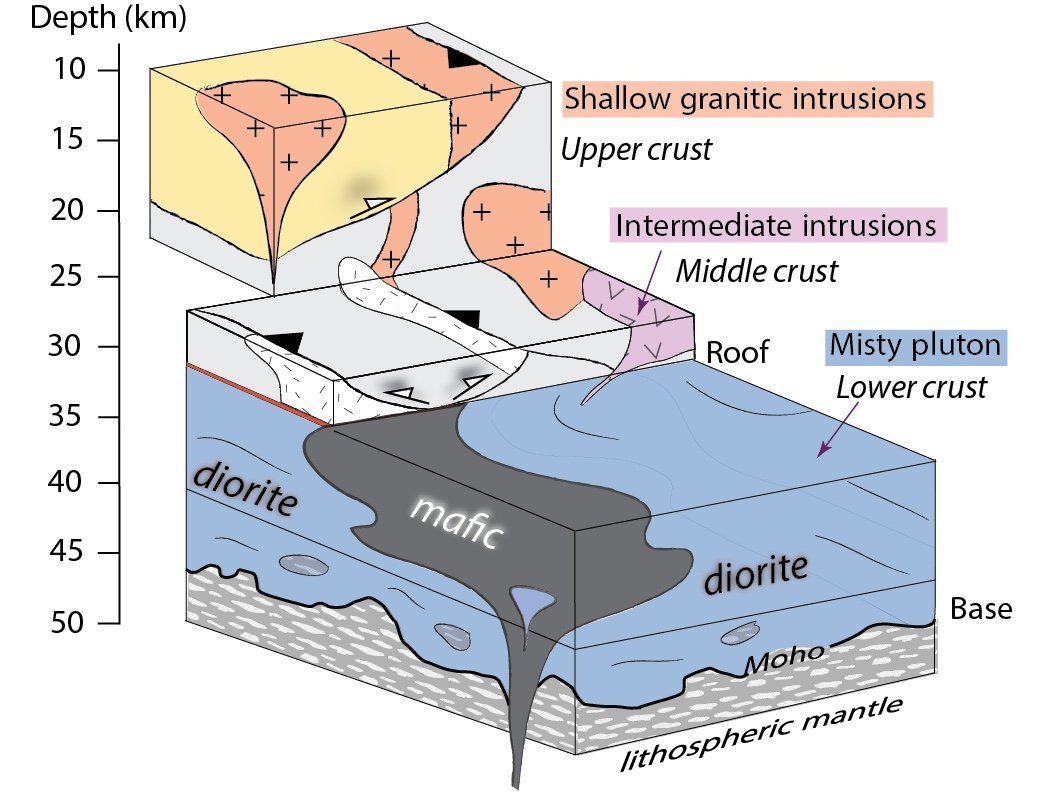

Block diagram showing the internal components of the Misty pluton, which is one of the plutons of the Southern Fiordland batholith. A conduit rising through the lithospheric mantle feeds a sheet-like basalt structure, which in turn connects to steep-sided granitic bodies in the middle and upper crust (colored in mauve and pink).

Outcrops of the Median Batholith

Western coastline exposure of the deepest, lower-crustal level shows steep feeder zones and conduits where mafic, crystal-rich magma was injected into lower-crustal diorites. Most of the rocks in the feeder zone here are hornblendites, which are composed almost entirely of hornblende. The hornblendites are thought to be modified products of mantle-derived melt.

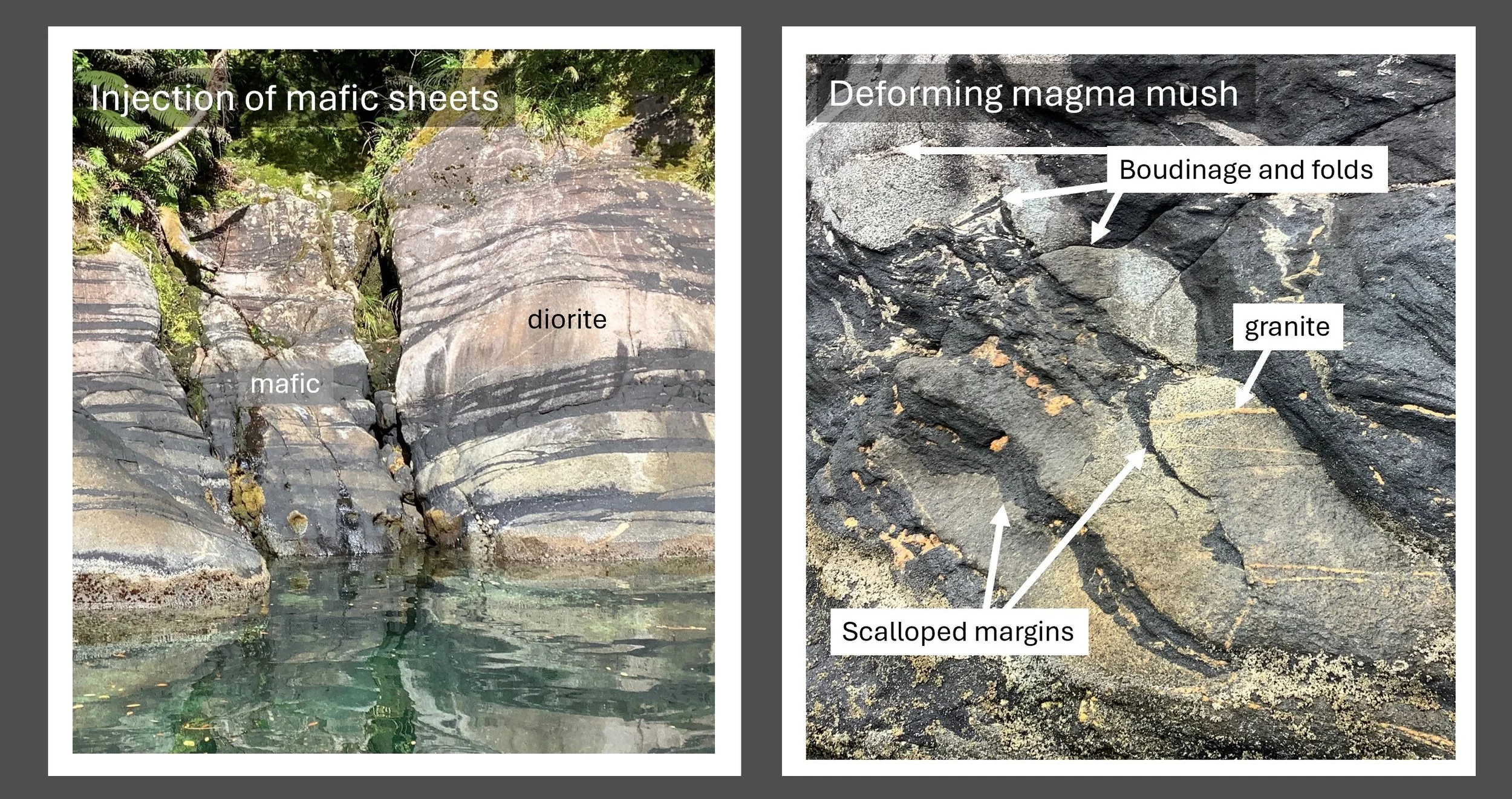

These rocks show the intrusion of dark mafic dike swarms into a deforming light-colored dioritic magma mush, where there is evidence of undulose margins and boudinage. The undulose margins and boudinage (the pulling apart of the igneous layers into fragments as the magmas deform) indicate that the mafic and dioritic magma were mingling and intruding together prior to their full crystallization at the base of the lower crust (depths of ~40 km). Granite dikes and veins that cut across the mafic and dioritic layers. This tells us that the granites arrived after the mafic and dioritic magmas had intruded and mingled and supports the idea that the intrusion of mafic magma helped release and mobilize granitic melts that were essentially trapped inside the dioritic mush. Textures such as these have led to the idea that cyclic intrusions help mobilize and move granite melts.

This outcrop shows mobilized granitic melts and mafic layers that have been pulled apart during deformation. Prior to the deformation, the dark material formed discrete layers, like those shown in the previous photo. The deformation shows that the different magma types were moving together as interacting mushes within the lower crust. Even more clearly than in the previous image, the granite cuts across both the mafic and dioritic units, further indicating that the granites were mobilized after the mafic dykes intruded the dioritic mush. As with the previous image, this supports the idea that sequences of mafic and dioritic intrusions help mobilize and move granite melts.

The curved, tightly folded white intrusion to the right of the geologist's hand in the photo shows that these rocks have been heavily deformed (pure shear). Structures such as these allowed the researchers to map a zone of compaction at the base of the crust. Evidence of compaction also appears in the photo on the right, where dark colored-layers are distorted and pulled apart.

Left photo courtesy of Joshua Schwartz

Outcrop of fully-fledged dikes and thick pegmatites that occur away from the base of the Misty pluton. The coherent structure of the intrusion suggests the magma was emplaced into a fairly well-crystallized host capable of exhibiting brittle-like breaking. A crystal-rich host results from fractional crystallization and the progressive removal of the remaining melt. The horizontal alignment of the crystals suggests that the host mush has been compacted and enough melt has been removed to enable the crystals to align. At the same time, the undulose margins of the dike and the exchange of the dark hornblende crystals across its margin indicate that, although crystal-rich, the host was not fully crystallized and could still exhibit ductile behavior. This supports the general picture that as the host mush becomes increasingly crystal-rich as melts are gradually extracted, the dikes that move magma through the crystallizing mush become more organized and regular in shape. The dyke here is about 30 cm across.

Further Reading

Allibone, A. H., et al. (2009), Plutonic rocks of western Fiordland, New Zealand: Field relations, geochemistry, correlation, and nomenclature, New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 52(4), 379 415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.2009.9518465

Brackman, A.J., et al. (2022), The formation of high-Sr/Y plutons in cordilleran-arc crust by crystal accumulation and melt loss: Geosphere, v. 18, no. X, p. 1– 24, https://doi.org /10.1130/GES02400.1.

Turnbull, R. et al. (2010), Field and geochemical constraints on mafic-felsic interactions, and processes in high-level arc magma chambers: An example from the Halfmoon pluton, New Zealand. Journal of Petrology, 51(7), 1477–1505. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egq026

Turnbull, R. E., et al. (2021), A hidden Rodinian lithospheric keel beneath Zealandia, Earth’s newly recognized continent. Geology, 49(8), 1009–1014. https://doi.org/10.1130/G48711.1