Tom Herring on High-Precision Geodesy

Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts.

There are three main types of geodetic measurement systems — satellite-based systems such as GPS, very long baseline interferometry (VLBI), and interferometric synthetic-aperture radar (InSAR). While each type of systems has its particular strengths, the cost of satellite-based receivers has plummeted. Millimeter-level accuracy will soon be incorporated into phones. This has broadened the kinds of geological questions we can now address with such systems. In the podcast, Tom Herring describes impressive geological applications as well as applications in civil engineering, such as dams and tall buildings, and agriculture.

Herring is a pioneer in high-precision geodetic analytical methods and applications for satellite-based navigation systems to study the Earth’s surface. He is a Professor in the Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The image shows Herring in front of a dam near the DMZ in South Korea where the concern was to be prepared for North Korea to breach dams on their side of the border in an attempt to flood South Korean infrastructure.

Podcast Illustrations

All images courtesy of Tom Herring unless otherwise noted.

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)

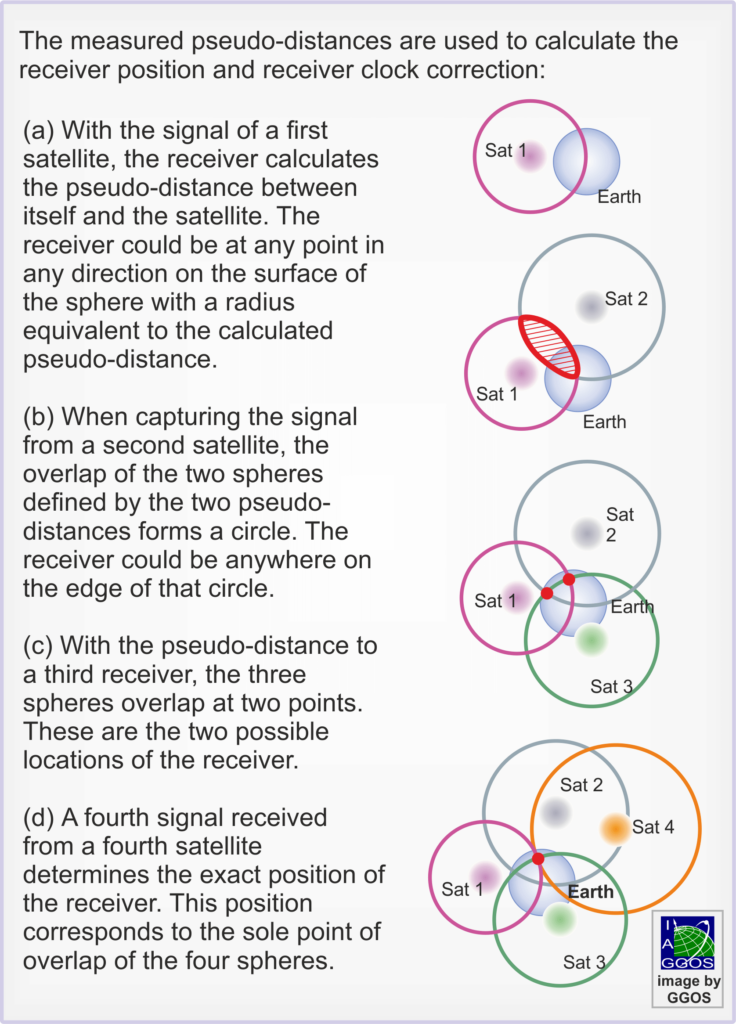

Principle of satellite-based position measurement. The distances are referred to pseudo-distances as they include errors from clock differences and atmospheric delays.

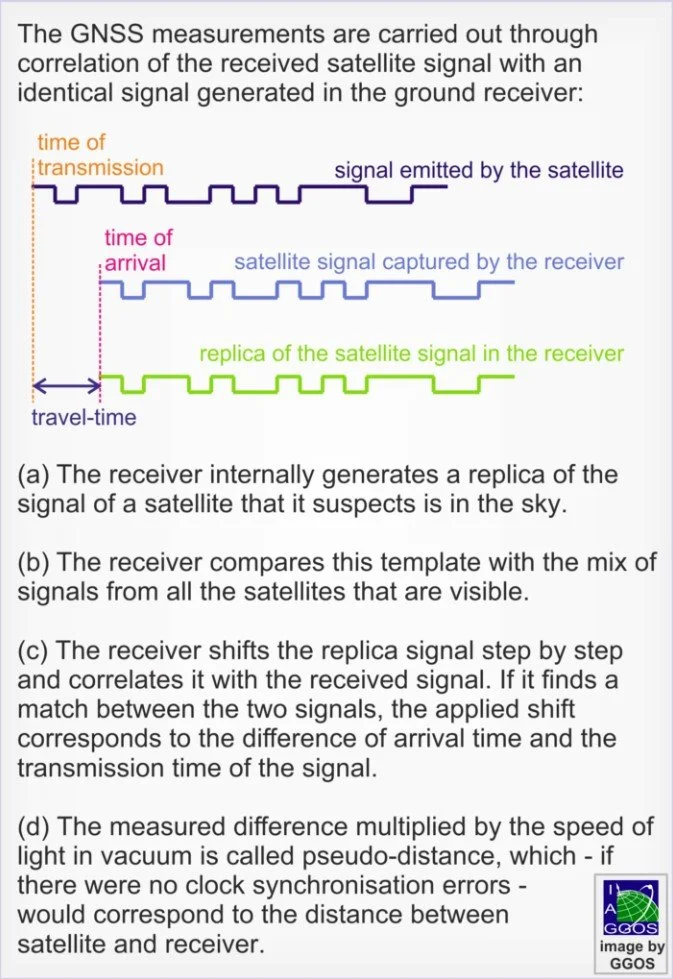

Four satellites are needed to estimate the 3D position and the receiver clock error. This feature allows the use of inexpensive clocks in the ground receivers. With more than four satellites (which is always the case now), atmospheric delays can be estimated. This is necessary in order to achieve mm accuracy positioning. The ionospheric delays are determined by making measurements at two (or more) frequencies. This exploits the fact that, at microwave frequencies, the refractive index of the ionosphere depends in a known way on the frequency.

Atmospheric layers alter the GPS signals and can introduce significant errors. The most important effects arise as the radio waves pass through the Earth’s charged ionosphere and water-laden troposphere. As Herring describes in the podcast, when four or more satellite signals are detected, the receivers can correct for atmospheric effects.

Inexpensive Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receiver costing $700. GNSS refers to a set of satellite-based systems such as GPS, the Russian GLONASS system, and the European Galileo system.

Expensive GNSS receiver costing about $20,000. The white plastic covers on both antennas are for the protection of the antenna elements. The antenna elements lie below the plastic in the center and sit on a metal sheet (that can’t be seen) called the ground plane. This reduces the noise from signals reflected from the ground underneath the antenna. Ideally, the antennas would see only signals coming directly from the satellites, not reflected ones. Reflected signals are a big problem for accuracy in urban canyons.

Permanent GNSS receiver in Oman where Herring has studied the subsidence of an oil and gas field during production.

Testing a GPS system on the roof of a tower on the MIT campus.

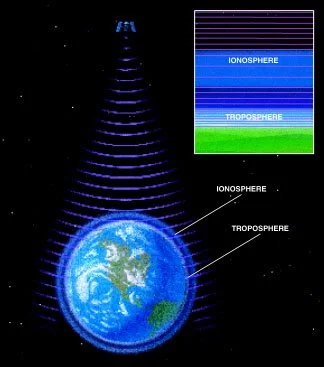

GNSS receiver installed in the Southern Alps of New Zealand to measure uplift rates across the Alps.

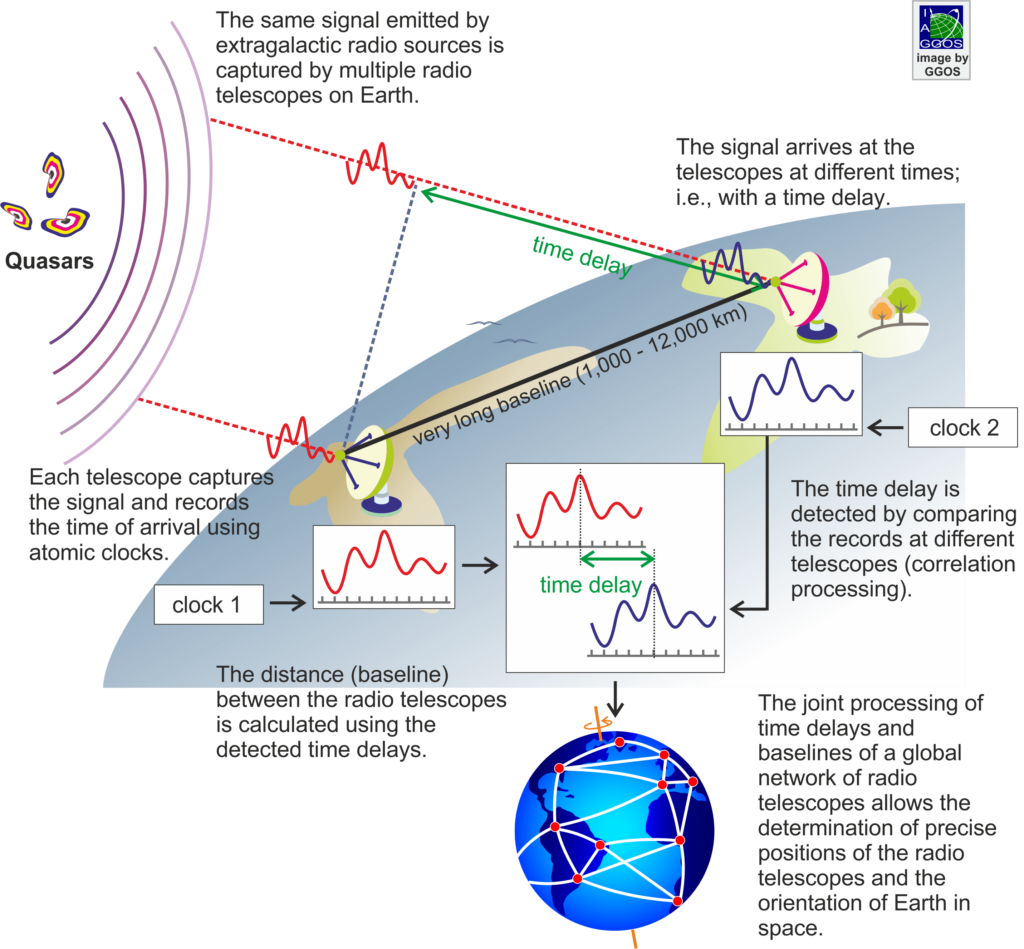

VLBI

Locations of VLBI antennas.

Applications of High-Precision Geodesy

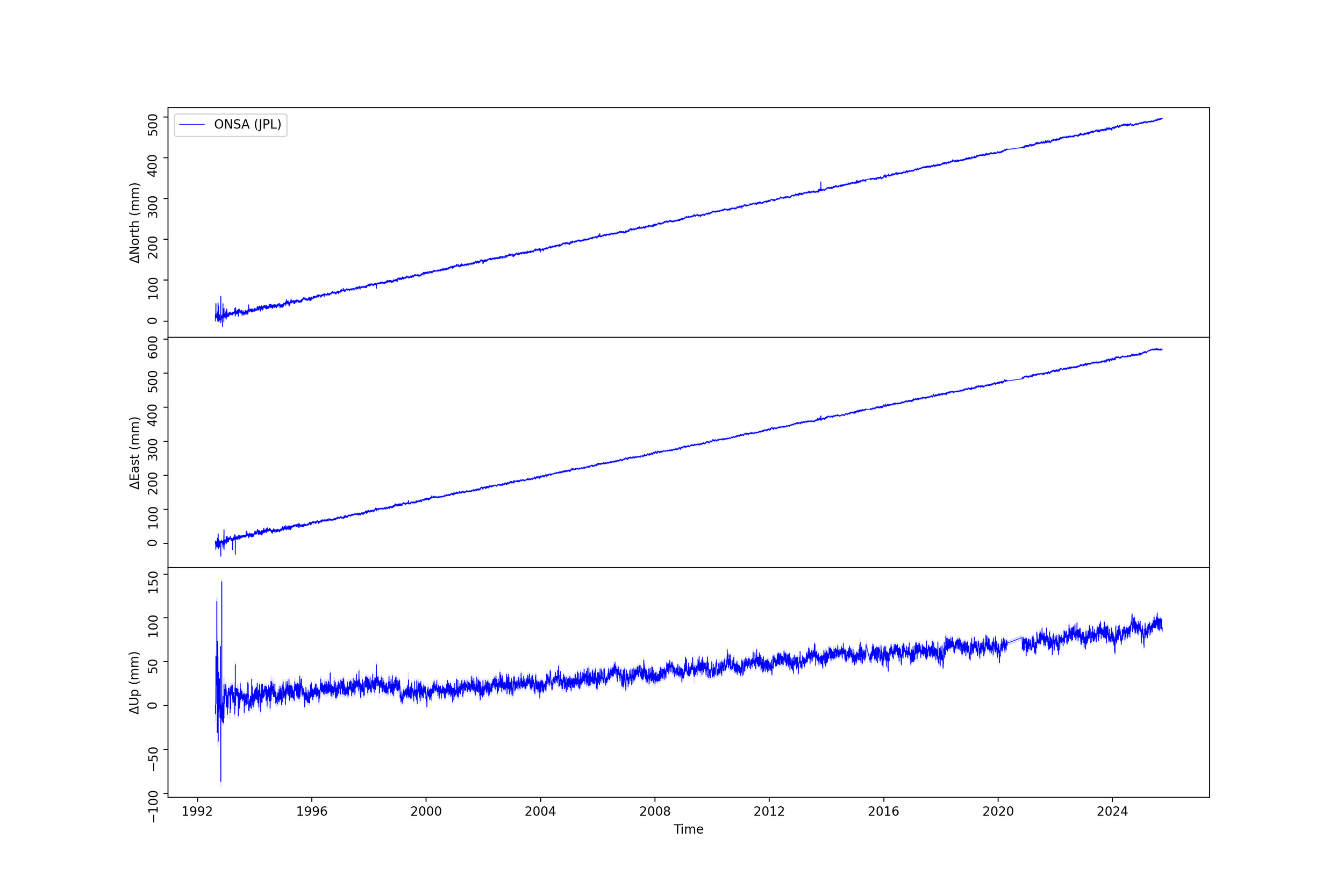

Measuring Isostatic Rebound

From top to bottom, GPS measurements of the northward, eastward, and vertical change in position of the Onsala Space Observatory, Sweden. The height uplift is 2.4 mm/yr, which is mainly caused by rebound following the melting of the Fennoscandia Ice sheet about 10,000 years ago.

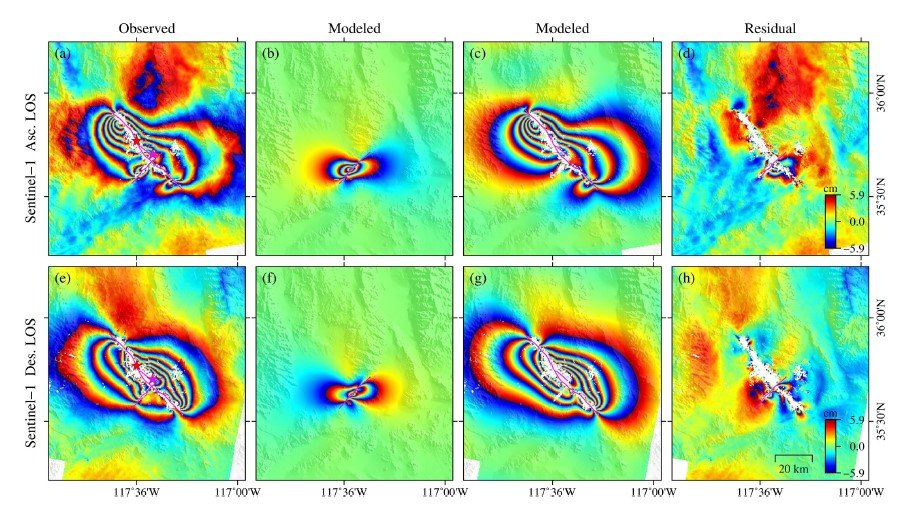

Ridgecrest Earthquake from InSAR and GPS

InSAR observations of the earthquake sequence (a Mw 6.4 foreshock and a Mw 7.1 mainshock), which struck Ridgecrest, southern California in 2019. The figure shows observed (a, e), modeled, and residual InSAR interferograms. (b) and (f) are modeled by the best-fitting foreshock-only and (c) and (g) are the corresponding results for the mainshock-only. The colors denote ground displacement along the line-of-sight from the spacecraft ranging from almost 6 cm (red) to -6m (blue). A color key is shown at bottom right in (h). The figures show phase measurements, which wrap through each cycle every 11.8 cm of displacement. Such measurements reveal a complex pattern of coseismic movement dominated overall by a right-lateral motion.

He, L. et al. (2022), Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 127, e2021JB022779

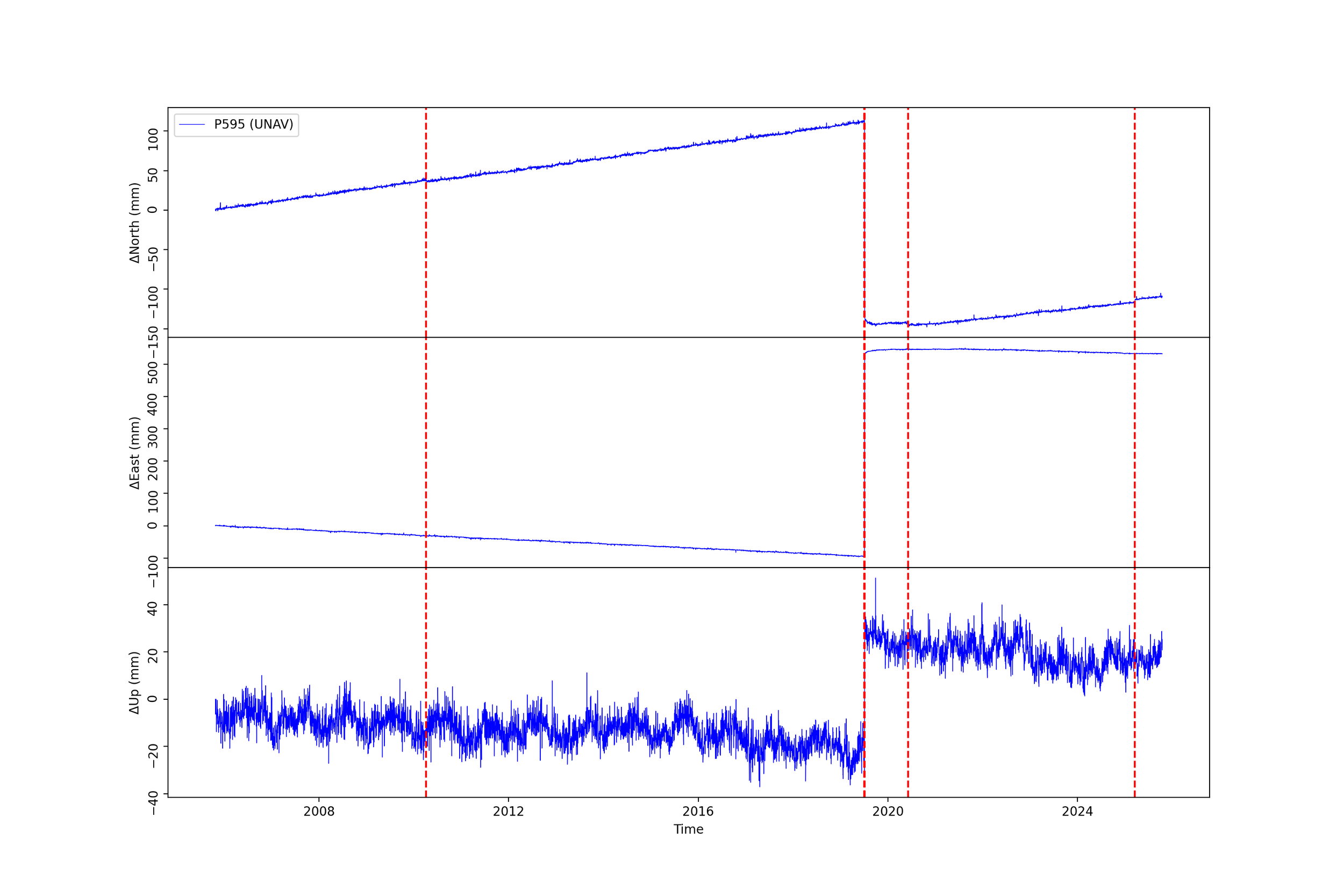

Position change in a North America fixed reference frame of a GPS sensor located close to the epicenter of the Ridgecrest earthquake between 2005 and 2025. Up to the time of the Ridgecrest earthquake, the site moved north at 8 mm/yr, west at 6.9 mm/yr, and sank slowly at -0.9 mm/yr. Since the total motions in height are much smaller, the noise and annual signals (probably from seasonal water changes) are more visible. This motion can be accounted for by the site’s proximity to the Pacific plate, which is moving to the northwest and exerting a drag on the North American plate. Earthquakes are marked by the dotted red lines, though only the Ridgecrest sequence is large enough to be visible at the scale shown. At the time of Ridgecrest, some of the accumulated stress is released, and the site jumps backward, i.e., in a southeasterly direction. The plots also show that the current velocity of the site is still quite different from what it was before the Ridgecrest earthquakes and averages 6.4 (N), 3.8 (W), and -3.6 (U).

The motions after the earthquakes are referred to as post-seismic deformation. Postseismic deformations are thought to come from continued motion on and around the fault that ruptured (especially around the beginning and end of the fault). These motions may involve slow slipping along the fault or viscoelastic flow caused by high stresses at the ends of the rupture.

Herring, T.A. et al. (2016), Reviews of Geophysics, 54 (4), 759

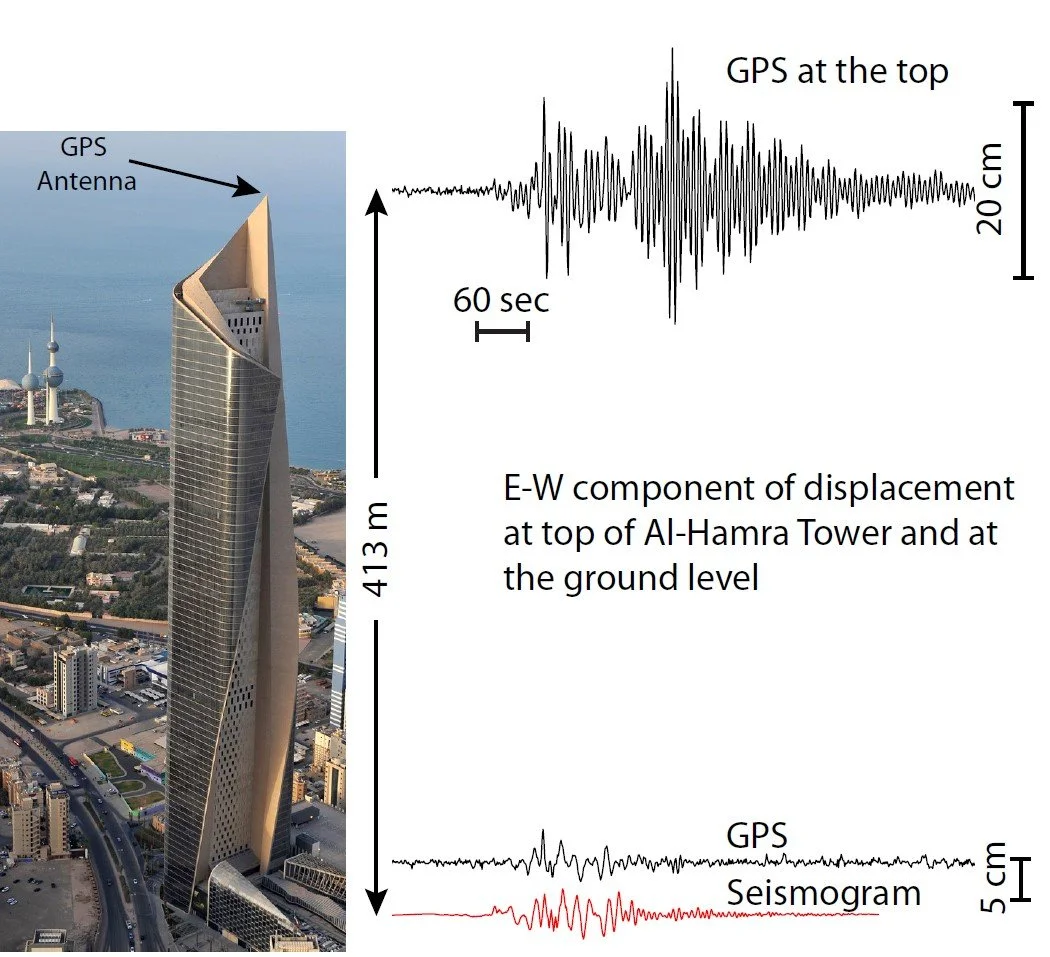

Tall Building Earthquake Effects

The Al-Hamra Tower in Kuwait City is 413-m tall with 86 floors. The measurements at right show the motion of the ground and the top of the building during a Mw 7.3 earthquake that occurred in 2017 642 km from Kuwait on the Iran-Iraq border. The top of the Al-Hamra Tower moved with amplitudes of up to 160 mm, up to four time larger than the ground motion amplitudes. Tower motions detected with GPS persisted for about 12.5 minutes after the seismic S-waves arrived at the tower.

Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill LLP

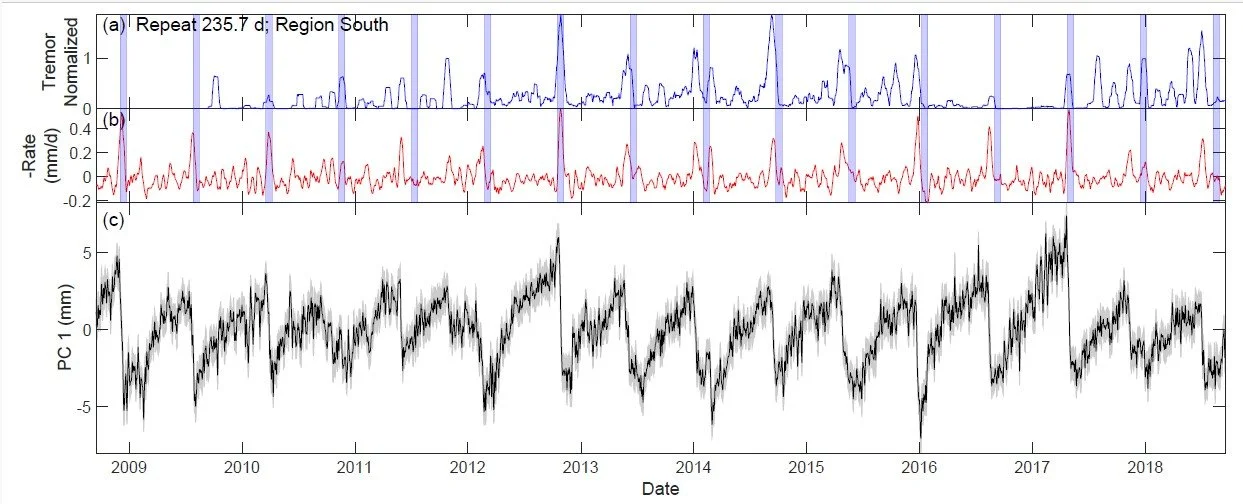

Slow Slip Events on the Cascadia Subduction Zone

The black trace at bottom shows the GPS time series of the common signal seen among all the sites in Northern California. The overall linear velocity has been removed, allowing the deviations from linear motion to be shown. The label PC 1 refers to the first principal component of the motion, which contains the signal most common to all sites. The top trace is the tremor count in the region of maximum slip, and the middle trace is velocity. The blue bands are spaced at 10-month intervals and are 21 days wide. They show how regular the peaks in slow-slip events are, much more so than most earthquakes. While the regular release of stress in smaller tremors suggests that large stresses leading to destructive earthquakes become less likely, these events transfer stress to other regions, possibly to shallower depths, which would enhance the likelihood of a damaging earthquake. Overall, this study shows that there is an area on the subduction zone interface that accumulates strain over about 10 months and then releases it over about 20 days. The elastic properties of the crust mean we can see the effects of this slip at depth on Earth’s surface.

India-Eurasia Collision

The map shows surface velocities relative to Eurasia as measured by GPS. The velocities show that half the India-Eurasia motion is accommodated across the Tien Shan in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Herring and his MIT colleagues were instrumental in getting the GPS network installed in this region.

Zubovich, A.V. et al. (2010), Tectonics, 29 TC6014

GPS velocity field with respect to the Eurasian plate. The red vectors indicate data from a network of Chinese GPS receivers, and the pink vectors are from other published results. Such results help constrain the various theories as to how the northward movement of India is accommodated. One particular controversy is the degree to which the movement is accommodated by slip along major bounding faults, such as the Karakoram fault or the Altyn Tagh fault. These results generally favor continuous crustal deformation rather than major movement along the faults.

Wang, W. et al. (2017) Geophysical Journal International, 208, 1088